film scoring

Film music is a stimulus that we hear but, by and large, fail to listen to,

a simple distinction that continues to inform the way we experience

music in film. As I will argue in Chapter 2, cultural biases that privilege

the visual over the aural condition our perception of film music as

peripheral to the visual image. The position of film music in the production

process (added after the editing) reinforces notions that music

is not a significant part of the apparatus that constructs filmic meaning.

But there is another reason, and one that I would like to address here,

for the prejudice against accepting music as an integral component in

the filmic process. Quite simply, few film spectators listen critically.

The skills necessary for critical listening are perceived in our culture

as present only in trained musicians. Yet the actual experience of

many “non musical” readers belies this assumption. Can you recognize

a melody (even if it’s performed in different versions), whistle or hum

a tune, sing “Happy Birthday,” keep time to a musical beat, and detect

mistakes in performance? These seemingly simple activities require a

substantial body of experience with music and a complex set of assumptions

about how it operates. I would like to offer a more global

model of musical perception, defining music as a construct of the mind,

a system whose basic properties are understood, either consciously or

unconsciously, by the entire set of individuals in a given culture, not

just a few. I A trained listener obviously will have more refined tools for

experiencing music than a listener without such training, but this is not

to say that music is comprehensible only to those who have formally

studied it. As music theorist Ray Jackendoff argues, “Musical expertise

is essentially a more refined and highly articulated version of an ability

that we all share.” 2

My purpose in this introductory chapter is to externalize the most

important components in the mental machinery that structures our

understanding of music, to offer a context by which to listen as well

as hear. This chapter is designed for a reader familiar with the analysis

of film but unversed in the basic principles of music. The essay which

follows is not a substitute for a musical education. It is a hands-on approach

to the film score as music. Because the vocabulary of musical

analysis may not be familiar, I define many terms as I use them. (Such

terms are denoted by boldface.) I have, however, assumed a certain degree

of familiarity with music and recommend that interested readers

supply themselves with a dependable music dictionary to accompany

their progress through the text.

Musical Language

Film music is above all music, and coming to terms with the filmic experience

as a musical experience is the first step in understanding how a

film’s score wields power over us. I would like to offer a selective analysis

of a cue from a classical Hollywood film score, Bernard Herrmann’s

main title for Vertigo, to demonstrate how one might begin to think

about a film score in musical terms. (The main title refers to the music

composed to accompany the opening credits.) Any printed text which

attempts to replicate a process from which it is fundamentally different

must confront the limitations of the printed word. The case of a text on

film music is a pronounced example. There is no substitute for listening

to music and I have specifically chosen a text which is widely available

as music. I hope that readers will take the opportunity to listen to it.

Although I have tried to include musical notation here and throughout

the text to stimulate the experience of listening, such notation is not

meant to substitute for it.

Music is a coherent experience, and because it is a system of expression

possessing internal logic, it has frequently been compared to

language. While a linguistic analogy is fraught with difficulty, it does, at

least on a preliminary level, help to reveal something fundamental about

how music works. like language and other systems of human communication,

music consists of a group of basic units, a vocabulary, if you

will, and a set of rules for arranging these units into recognizable and

meaningful structures, a grammar. The pitches themselves constitute

The Language of Music 5

the vocabulary of the system and harmony the grammar for organizing

them. like language, music is also a culturally specific system. The

Western world, especially from the eighteenth century through the

twentieth, has organized music around a single note, called the tonic,

which serves as a focal point for its structure. “All other pitches are

heard in relation to this pitch and it is normally the pitch on which

a piece must end.”] Tonal music or tonality, the system of music

derived from this principle, constitutes one possible way of organizing

music. It will, however, be the system of music explored here as it is

the system which forms the basis of the classical film score.

In tonal music, the pitches or notes may be combined horizontally,

that is, in succession, or vertically, that is, in simultaneity.4 The most

familiar strategy for organizing notes horizontally is melody, which can

be defined as an extended series of notes played in an order which is

memorable and recognizable as a discrete unit (hummable, if you will).

One of the most distinguishing characteristics of tonal music since about

the middle of the eighteenth century is the extent to which melody is

privileged as a form of organization. its presence prioritizes our listening,

subordinating some elements to others and giving us a focal point

in the musical texture.

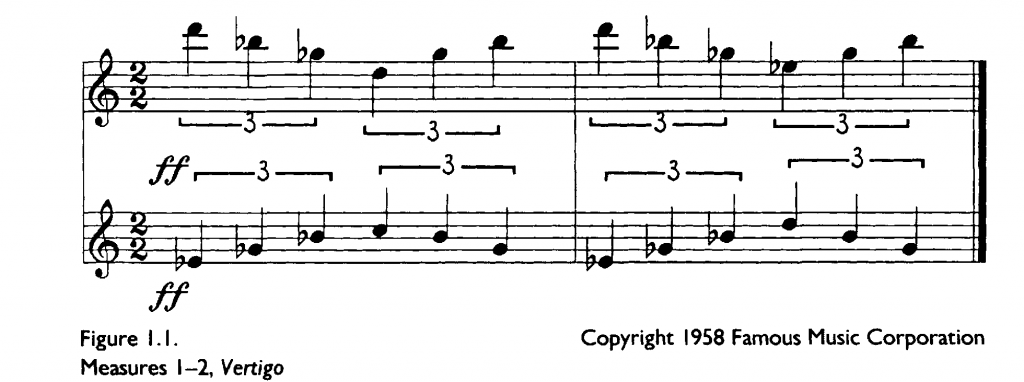

How does melody, as an organizing construct, figure in the main title

of Vertigo~ It largely doesn’t. One of the most identifying characteristics

of Vertigo’s score, indeed of most of the Herrmann Hitchcock oeuvre,

is the absence of hummable melody. (Try whistling the shower scene

from Psycho [1960] or the main title from North by Northwest [1959].)

Herrmann begins Vertigo with a musical figure associated in the film with

vertigo itself, alternately descending and ascending arpeggiated chords

played in contrary motion in the bass and treble voices. This may sound

rather technical and somewhat daunting but a quick look at Figure 1.1

may make this description clearer. Notice how in the top part of the

composition, the treble voice, the musical notation moves down and

then up, while in the bottom part, the bass voice, the musical notation

moves up and then down; in other words, they move in opposite

directions or in contrary motion. The chords here are described as

arpeggiated because in both the treble and bass voices the notes of

the chord are played in succession (or horizontally) instead of simultaneously

(or vertically). Ultimately, this figure resists definition as melodic

(I, for one, have trouble even humming it) in three ways: the contrary

directions it incorporates defeat a sense of linearity inherent in the concept

of melody; both parts are equally important musically (which one

is the “melody,” the treble voice or the bass voice?); and the arpeggiated

chords themselves are unstable and shifting harmonic constructions.

s Herrmann’s main title for Vertigo, as we shall see, is unnerving

in the context of tonal music. One of the reasons for the discomfort

of the opening is the absence of a conventional melody, which denies

the listener the familiar point of access.

Harmony is an equally important component of musical language and

one which figures importantly in the Vertigo example. Harmony can

be defined as a system for coordinating the simultaneous use of notes.

(Generally, three or more notes sounded simultaneously are known as

a chord.) Tonal harmony privileges those combinations of notes described

as consonant, which do not require resolution, over those

combinations described as dissonant, which do require resolution.

Consonance and dissonance underlie tonal music’s patterns of tension

and resolution enacted through chordal structures that deviate from

and ultimately return to the most stable and consonant of all chords in

the harmonic system, the tonic chord, or a chord built on the tonic

note. In tonal music the desire to return to the tonic chord for a sense

of completion is so great that to deny it at the end of a piece of music is

to constitute an intense disruption. An example of a score that exploits

this desire is Michel Legrand’s music for Jean-Luc Godard’s Vivre sa vie

(1962). Though tonal, the score fails to offer the tonic chord in each of

the dozen times musical accompaniment occurs in the film.6 Expectation

concerning a resolution becomes so strong that at the end of the film.

when the tonic chord is missing even from the music which accompanies

the closing credits. a common reaction among listeners is to turn

to the projector. wondering if a mechanical breakdown or faulty print

is the cause of this deliberate act of musical irresolution.

Vertigo is a score which exploits harmony for disturbing effect. Its

opening. as we have seen. is formed by arpeggiated chords. I’d like to

return to Figure I. I and be musically specific for just a moment. These

are seventh chords. which include and draw attention to the seventh

and least stable note of the scale. Contributing to the dis-ease created

by the seventh chords are the intervals constructed by the intersection

of the bass and treble voices. An interval may be defined as the

relationship between any two given notes. measured according to the

number of notes that span the distance between them. In this example

from Vertigo the opening notes in the bass and treble voices form an

extremely grating interval. the major seventh. and the point at which

the arpeggiated chords come closest together forms a major second.

another dissonant interval. The specifics of the preceding analysis are far

less important to remember than the main point: Herrmann has created

a harmony to disturb tonality. Royal S. Brown has compellingly argued

that the scores Herrmann composed for Hitchcock are distinguished by

exactly this kind of “harmonic ambiguity whereby the musical language

familiar to Western listeners serves as a point of departure.” The extent

of this ambiguity is almost immediately discernible to the ear. “Norms

are thrown off center and expectations are held in suspense for much

longer periods of time than the listening ear and feeling viscera are

accustomed to.”7 There is something quite unsettling about listening to

Vertigo. and at least part of that something is its harmonic structure.

Musical Affect

The main title for Vertigo is disconcerting in a number of ways. musically

speaking. I have been analyzing its basic structure as music. the

way it avoids melody as a construct of organization and the way it

bends the syntactical “grammar” of harmony. Music, however, means

on a number of levels, and like other systems of human communication

it is capable of producing meaning outside of itself. Expressivity is not

intrinsic or essential to music: yet as any listener can attest music may

and often does arouse an emotional or intellectual response. What is

the source of music’s expressivity, its ability to produce extramusical

meaning in its listeners~ In a pioneering study published in 1956 musicologist

Leonard B. Meyer encapsulates the problem in equating music

too closely with a language system.

Not only does music use no linguistic signs but, on one level at least, it

operates as a closed system, that is, it employs no signs or symbols referring

to the non-musical world of objects, concepts, and human desires.

Thus the meanings which it imparts differ in important ways from those

conveyed by literature, painting, biology, or physics. Unlike a closed, nonreferential

mathematical system, music is said to communicate emotional

and aesthetic meanings as well as purely intellectual ones.8

The question of how music can stand for concrete and identifiable

phenomena when its method of signification is neither direct nor inherent

is one not yet fully theorized. The mechanism by which music

encodes meaning has been an object of study in a variety of disciplines

including musicology, physiology, anthropology, sociology, cognitivism,

psychoacoustics, and psychoanalysis. One of the most popular of these

arguments is the one articulated by Deryck Cooke in 1959 which posits

the existence of precise relationships between intervals and emotions.

For instance, the major third connotes “joy,” while the minor third,

“stoic acceptance, tragedy.” 9 More recently, cognitivists have theorized

musical affect as the result of a response to musical structure. Arguing

along lines laid out by Meyer, Ray Jackendoff suggests that musical affect

is “a function of being satisfied or surprised by the realization or violation

of one’s expectations.”‘o Jackendoff’s argument is predicated upon

the premise that perception is largely unconscious and that in some

sense we are “always hearing the piece [of music] for the first time.””

Regardless of its source, music’s ability to produce specific effects

is undeniable. One of the most demonstrable of the ways in which

music can have a definite, verifiable, and predictable effect is through

its physiological impact, that is, through certain involuntary responses

caused by its stimulation of the human nervous system. The most important

of these stimulants-rhythm, dynamics, tempo, and choice of

pitch-provide the basis of physiological response.

The power of rhythm has frequently been traced to primitive origins,

music “borrowing” from human physiological processes-heartbeat,

pulse, breathing-their rhythmic construction. Rhythm organizes

music in terms of time. The basic unit of rhythm is the beat,

a discernible pulse which marks out the passage of time. Since the

Renaissance, rhythm has been characterized by regular patterns of beats,

usually composed of groups of twos or threes. The term meter refers

to the way these units are used to organize the music, providing a kind

of sonic grid against which a composer writes. Western art music is

characterized by a high degree of regularity in terms of both rhythm,

that is, the patterns themselves, and meter, that is, their organization.

Regular rhythms, perhaps because of their physiological legacy, and certainly

because of the way they have been conventionalized, can be

lulling and even hypnotic because of the familiarity created through their

repetition. Irregular or unpredictable rhythms attract our attention by

confounding our expectations and, depending on the violence of the

deviation, can unsettle us physiologically through increased stimulation

of the nervous system.

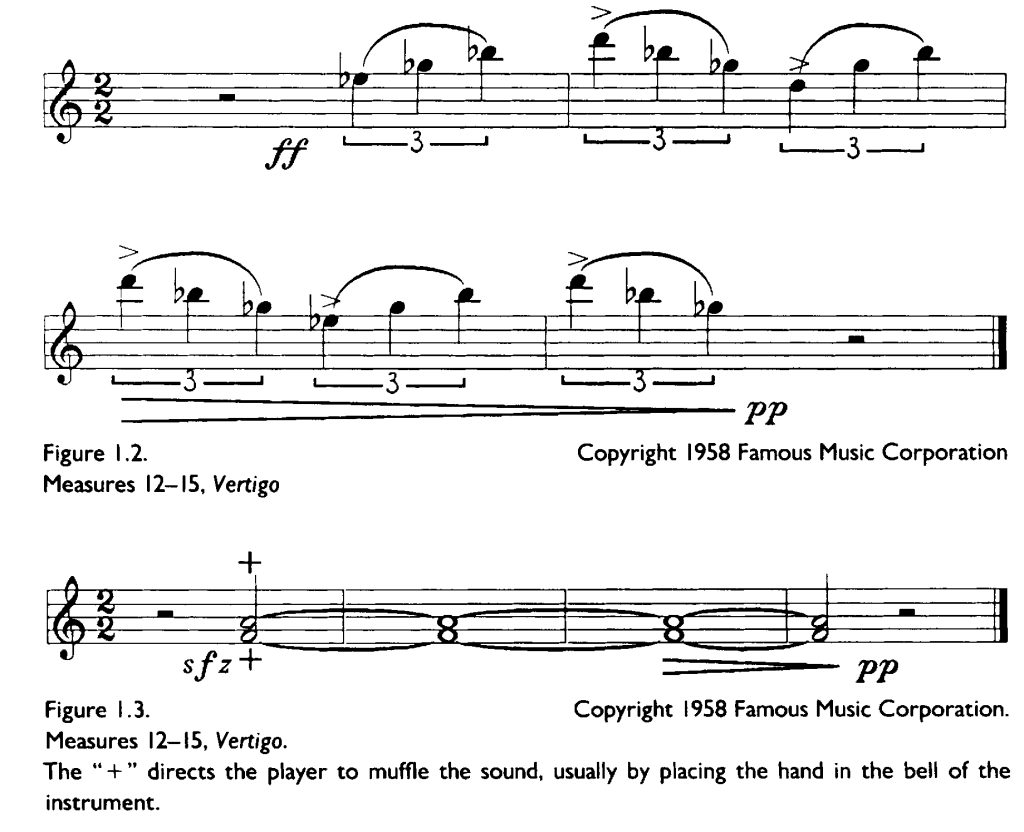

In Vertigo Herrmann confuses a clear perception of rhythm. The metrical

organization of the main title is a duple meter, or one in which

there are two beats to the measure. Conventionally, such a meter would

cause the primary accent to fall on the first beat of each measure, creating

a rhythm of alternating accented and unaccented beats (something

like a trochee in English metrical verse). And, in fact, for most of the

main title, the first beat carries the accent. At certain points, however,

Herrmann displaces this point of emphasis for disturbing effect. In measures

12 to 15, for instance, he begins a restatement of the arpeggiated

chord in the flutes on the second beat of the measure, instead of the

first, which disturbs the pattern. Notice the presence of a rest, the

musical notation for silence,

at the beginning of the first

measure in both Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3. Herrmann emphasizes this

displacement through the use of the sforzando (sfz). a sudden. loud

attack on a note or chord. on the second beat in the horns (Fig. 1.3).

Besides avoiding identifiable melody and flirting with tonal ambiguity.

the opening moments of the score exploit the effects of an unpredictable

rhythmic change which contributes to the agitation many listeners

feel in hearing this cue.

The most obvious way in which music or any type of sound can elicit

a direct response is through its dynamics. or level of sound. Volume

reaches the nervous system with distinct impact. increasing or decreasing

its stimulation in direct proportion to its level. Extremes in sound

are the most noticeable dynamic because of their pronounced divorce

from the natural sound level of everyday life. Extremely loud music can

actually hurt the listener. while extremely soft music tends to drop out

of the range of human perception. Crescendos and decrescendos. or

the increase and decrease in the volume of sound. respectively. help to

modulate the stimulation and can be used to heighten or diminish it.

Quick and unexpected changes in dynamics intensify this process.

Herrmann’s main title clearly demonstrates the effect of volume. By

juxtaposing fortissimo (very loud) and pianissimo (very soft) both

successively and simultaneously, Herrmann creates discernible effects in

us. Listen for the change in dynamics at the beginning of the main title.

Measures 1-8, for instance, contain six measures (1-6) of sustained fortissimo

(denoted ff) followed by only two measures (7-8) to decrease

the sound level to pianissimo (denoted pp). Although this passage contains

a decrescendo to help modulate this change, the asymmetry, if you

will, of the sound dynamics keeps us off guard musically.

Tempo modulates the speed with which a piece of music is performed.

Quick tempi tend to intensify stimulation of the nervous system;

slow tempi tend to dissipate it. Diverging from a characteristic pace can

also cause a physiological response. The accelerando and ritardando,

a speeding up and slowing down of the musical pace, respectively, help

to control such response, heightening, sustaining, or diminishing it.

In the main title of Vertigo the tempo is basically regular (Herrmann

marks it “Moderato Assai” in his score), but it does incorporate

a sudden change in its second half which has the effect of doubling the

tempo. Near the end of the main title (at measure 53 to be exact)

the arpeggiated chord is heard twice as fast as its previous occurrences.

Herrmann has accomplished this effect by cutting each note value in

half. Where the motif had initially taken a full measure to perform in

the violin part (Figure IAA), it can now be performed twice in the

same amount of time by the harps (Figure lAB).

Even choice of pitch can elicit response. Herrmann frequently manipulated

pitch to create anxiety. The shower scene in Psycho, for

instance, is scored for violins; the players execute upward glissandi culminating

in the highest note in the pitch system. In the scene which

precedes it, notes of extremely high pitch erupt out of the musical tapestry

often an octave or more above the musical line which precedes

or follows them. In the main title of Vertigo a six-note rising and falling

figure is played high in the violins’ register. It is set off against the extremely

low pitch of the tubas, not only exploiting the effect of pitch

but combining it with the dis-ease created by splitting the listener’s

attention between widely divergent musical registers.

Musical Conventions

One of the best ways to understand the power of music is to study

the conventions by which musical affect circulates through a culture.

A musical convention harnesses musical affect to specific and concrete

meaning through the power of association. Musical conventions which

become ingrained and universal in a culture function as a type of collective

experience, activating particular and predictable responses. In

tonal music, for example, an habanera rhythm

is a musical

convention which summons up thoughts of Spain. Harmonic structures

such as open fourths and fifths are used to represent ancient Greece and

Rome. Quartal harmony, based on the interval of the fourth, suggests

the Orient. To an overwhelming extent, the classical score relied upon

such conventions. Composers, working under the pressure of time,

used familiar conventions to establish geographic place and historical

time, and to summon up specific emotional responses predictably and

quickly. The fact that musical conventions are often arbitrary seems of

little consequence. The habanera rhythm associated with Spain is actually

of Cuban origin (via a French composer); the open fourths and

fifths associated with the classical age are modern conjecture; quartal

harmony is not used exclusively in music of the Orient. But for all their

lack of authenticity, conventions are nonetheless powerful.

The classical Hollywood film score relied largely on the resources of

the standard symphony orchestra with unusual instruments added for

particular effects. Thus at its disposal was a veritable arsenal which could

be tapped to activate specific associations. The string family, for instance,

because of its proximity in range and tone to the human voice, is thought

to be the most expressive group of instruments in the orchestra. For

this reason strings are often used to express emotion. In particular, the

violin is characterized by its ability to “sing” because its timbre or tonal

quality is close to that of the human voice. In the opening sequence of

God Is My Co-Pilot (1945), for example, Franz Waxman uses violins to

add emotional resonance explaining, “[for a] deeply religious, emotional

tone … I used massed violins playing in a high register to convey the

feeling.” 12 Herrmann, on the other hand, in Psycho, exploits these associations

for ironic effect: the entire score of this chilling thriller, one of

Hitchcock’s grisliest films, is composed for a string orchestra.

Horns, with their martial heritage, are another obvious example. Because

of their link to pageantry, the military, and the hunt, horns are

often used to suggest heroism. Says Henry Mancini, “The most effective

and downright thrilling sound is that of all of the [brasses] playing

an ensemble passage.” 13 Erich Wolfgang Korngold, who was known for

his use of brass instruments, exploits a complement of horns for the

rousing main title of Captain Blood. John Williams relies on horns in the

epic Star Wars trilogy to suggest the heroic nature of this futuristic saga.

Even a contemporary score like RoboCop’s (1987) exploits the conventional

associations of the horns, using different c.ombinations of brass

instruments to accompany the death-defying deeds of the robocop.

Rhythm, like instrumentation, can also provoke specific responses.

Dance rhythms, in particular, can be very evocative. Thus, when Herrmann

in The Magnificent Ambersons characterizes the Ambersons with

a waltz, he is employing a familiar convention to project the sense of

grace and gentility that the family symbolizes. When Waxman bases

the theme music for Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard (1950) on

a tango, he is characterizing her as steamy, sultry, Latin. and in 1950,

conspicuously out of date. Carlotta’s theme in Vertigo exploits the fiery

and passionate associations of the habanera rhythm, transferring to the

icy exterior of Kim Novak’s fragile Madeleine the sensuality of her psychic

ancestor, Carlotta. Musical conventions are profuse and can even

be intercepted by a personal response, but to overlook their effect is

to ignore the power of collective association in human perception. Film

music, when it taps this source, is appealing to a strong response that

can impact spectators whether they are consciously aware of it or not.

A crucial site for the acquisition of a culture’s musical conventions

is the cinematic auditorium itself where musical effects are combined

with visual imagery to reinforce them. In fact, for spectators who are

basically unversed in art music, films are the major site for the transmission

of a culture’s musical conventions. The association of tremolo

strings (the sustaining of a single note through rapid repetition) with

suspense, for instance, is a response acquired, in all likelihood. not from

an acquaintance with the musical idiom of the nineteenth century, where

it is earlier exemplified, but from film scores which exploit it. One

of the most interesting aspects of Herrmann’s score for Vertigo is the

way it avoids the most obvious musical convention for suspense, tremolo

strings, and exploits subtler techniques for the creation of tension such

as harmonic instability, shifting and unpredictable rhythm, tempo, and

dynamics, and absence of conventional melody.

Music and Image

Our experience of music in film is shaped by both its constitution

as music and its function as an aural accompaniment to visual images.

Film music shares with music composed for performance in the concert

hall its basic underlying structure as music as well as its power of expressivity.

But film music is part of a dual discourse which incorporates

both an aural and a visual component. The first step in an analysis of film

music is to hear it as music; then it becomes necessary to analyze it as

a part of a larger construct, that is, to analyze film music in conjunction

with the image and sound track it accompanies. Issues involved in the

relationship between music and image and the theory that underlies it

are treated in more depth in the following chapter. Let me here simply

point to the nature of that relationship and its consequences for the

Vertigo example.

Film music obviously does not exist in a vacuum. It shares with the

image track (and other elements of the soundtrack) the ability to shape

perception. Film music’s power is derived largely from its ability to tap

specific musical conventions that circulate throughout the culture. But

that power is always dependent on a coexistence with the visual image,

a relationship bounded by the limits of credibility itself. Imagine a perfectly

innocuous setting, an eighteenth-century drawing room where

two lovers are reunited after numerous narrative complications. But

instead of a soaring melody played by an offscreen orchestra, we hear

tremolo strings and dissonant chords. Our tendency as spectators would

be to perceive that music as meaningful, specifically to read the scene as

suspenseful. We might even expect some kind of narrative complication

or even a visual shock because of the music. If these expectations are

thwarted, most spectators would feel manipulated, even cheated. Craig

Safan, a contemporary film composer, explains it in these terms: “You

excite an audience in a certain way and if you betray them they won’t

want to see your movie. And musically, you can betray your audience.

You have to be very careful about that.” 14 Music and image collaborate

in the filmic process. The farther music and image drift from a kind of

mutual dependency, the more potential there is for the disruption or

even destruction of the cinematic illusion.

The music for the main title of Vertigo plays out against a series of

brightly colored geometric spirals which spin against a black background.

Hitchcock films often give Herrmann’s main title free rein by overtly

drawing attention to the music through abstract visual constructions.

(Psycho and North by Northwest are two other examples.) In Vertigo the

correspondence between the circularity of these images and the film’s

title is obvious, but it is equally important to note the relationship between

these images and Herrmann’s music. Vertigo’s opening consists of

alternately descending and ascending arpeggiated chords played in contrary

motion in the bass and treble voices. At this point I would like to

define it as a motif, a distinctive musical passage that is repeated (and

varied) throughout a musical text. This motif progresses in time without

establishing a clear direction (neither up nor down) or, as discussed

earlier, a clear harmony (hovering dangerously close to an abnegation

of tonality). It is an almost uninterrupted undulation from beginning to

end. This quality of the music is, interestingly enough, reflected graphically

in its very notation. It is Herrmann’s mesmerizing evocation of

dizziness. Spinning in time with the spiraling geometric forms, the motif

reinforces and is in turn reinforced by the vertigo suggested by the

images.