Harmony

A Beginner’s Guide to 4-Part Harmony: Notation, Ranges, Rules & Tips

As you slowly advance in music theory and composition, you will inevitably run into 4-part harmony. This is an important element of the musical language of the Classical masters from Bach, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven and beyond. The concept developed over centuries and is still used to this day.

So what is four-part harmony? Four-part harmony is a traditional system of organising chords for 4 voices: soprano, alto, tenor and bass (known together as SATB). The term ‘voice’ or ‘part’ refers to any musical line whether it is a melody sung by singers, a long note played on an instrument or anything in between.

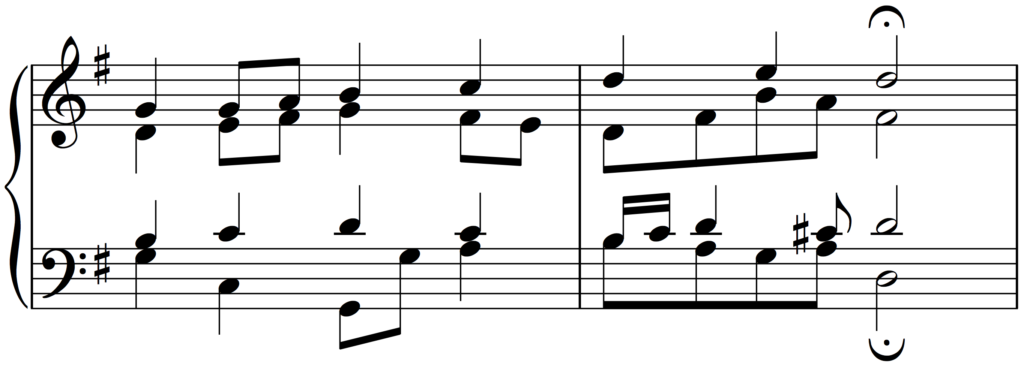

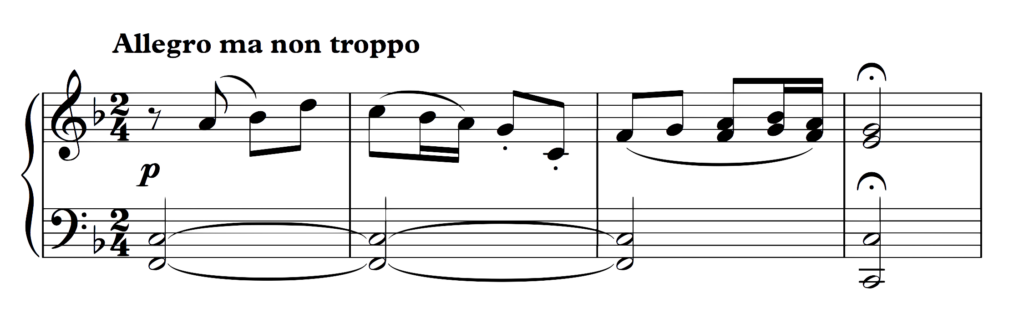

Here’s a brief example of 4-part harmony from the music of J. S. Bach. Notice that there 2 main aspects to it. Firstly, there are 4 voices and each one is singing a melody. This is the melodic, or the ‘horizontal’, aspect of the music.

Secondly, the four voices are singing at the same time so their notes are combined into one sound. At any one moment, the music consists of 4 voices each singing one note. In other words, the voices are producing 4-note chords. This is the harmonic, or the ‘vertical’, aspect of the music.

The harmonic (or ‘vertical’) aspect and the melodic (or ‘horizontal’) aspect work together.

In four-part harmony, we deal with both these two aspects at the same time. We get four distinct parts held together by the same chord progression.

Why Four-Part Harmony?

While music for 2, 3, 5, 6 and more voices does exist, 4-part harmony became standard in the musical style of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries (a period known as the Common Practice Era). The reasons for this are quite practical:

- Four-part harmony developed as tonal music became standard (that’s the musical system of the major and minor keys). As you know, this type of music mainly works with our typical major and minor chords and these chords fit really well into 4 parts. Tonal music and four-part harmony complement each other perfectly.

- Four-part harmony also accounts for the whole range of human voices: from the lowest notes (sung by males) to the highest (sung by females) and everything in between.

Because of these reasons, even instrumental or orchestral music of the time was written with four-part harmony in mind. The orchestral strings, for example, are often treated as a four-part choir: 1st violins on top, then the 2nd violins and violas in the middle, and cellos plus double basses together for the lowest part.

The orchestral strings are often treated as a 4-part choir

Why do we Learn a Musical System of the Past?

Now before we move on to the basics of four-part writing, why should we even learn a musical system of the past?

The answer to this question merits its own article but in short, it’s because:

- The discipline you get from manipulating musical notes in certain ways according to certain guidelines can be applied to any other musical style. The study of four-part harmony teaches you how music works (by working with aspects such as chord progressions, rhythm and writing melodies). You can then apply your understanding in any way you like in your own music.

- Four-part harmony is part of a continuous line of musical development from the earliest medieval chants to contemporary film music. When you see how music composition developed over time, you get a profound appreciation of how it evolved to fit the needs and purposes of its time. Four-part harmony is an important part of this evolution.

- In addition, learning how composers of the past wrote their music opens it up for analysis and further learning. Earlier we looked at a brief excerpt from a Chorale by Bach (whose music is the standard model for 4-part writing). Thinking about why the composer chose to do things in one way or another provides composition lessons that no book or course can teach us!

Later on in this lesson, we’ll come back to the same Bach example and see what it can teach us about the basics that we are learning today.

How to Write 4-Part Harmony: the Basics

Writing basic 4-part harmony requires some fundamental guidelines for: 1) proper notation, 2) the ranges of the voices, 3) doubling rules and 4) spacing. Let’s go over these one by one.

The Notation

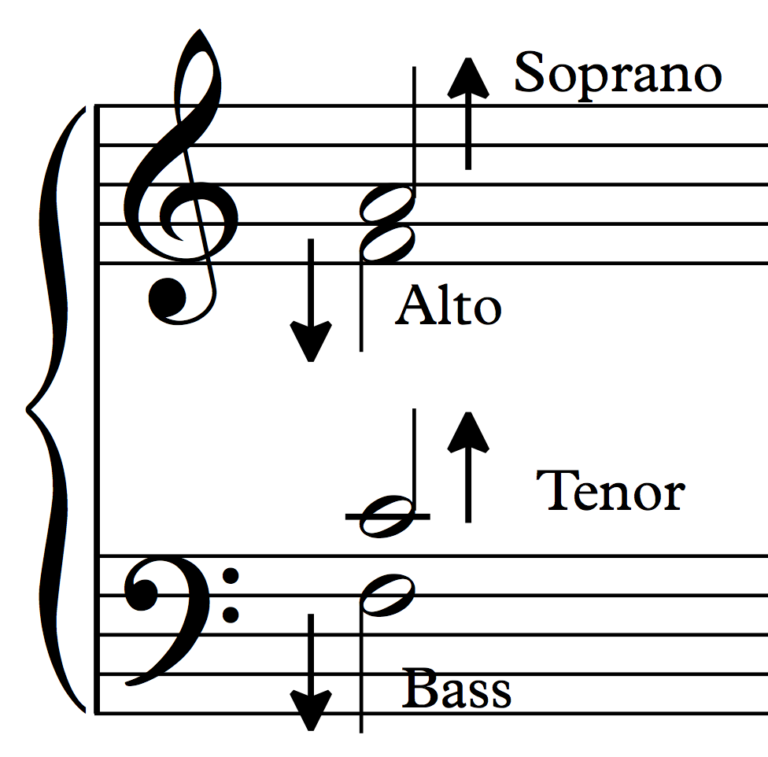

As we said, 4-part harmony is written for 4 voices: Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass (SATB in short). The notation for these is written on two staves: one in the treble clef for the Soprano and Alto parts and the other in the bass clef for the Tenor and Bass parts.

To make the written music clear, the soprano voice must have notes with stems going up while the Alto voice must have notes with stems going downwards. Similarly, the Tenor voice must have stems going up and the Bass voice with stems going down.

Notation for four-part harmony

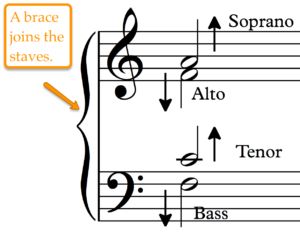

Also, the two staves are joined together by a brace, showing that they go together:

In four-part harmony, the staves are joined by a brace.

Four-Part Harmony Voice Ranges

Here are the ranges of the four voices. More or less, these represent the normal span of human voices and it’s not recommended to go beyond.

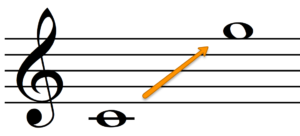

Soprano: from middle C to high G

The range of the Soprano voice for 4-part harmony.

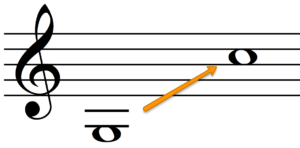

Alto: from G below middle C to C above middle C

The range of the Tenor voice for 4-part harmony.

Bass: from F below the stave to middle C

The range of the Bass voice for 4-part harmony.

Four-Part Harmony Doubling Rules

If basic chords are constructed of three notes but this style of harmony is in four parts, where does the fourth note come from? That’s a good question and a common one too. The answer is in a procedure known as doubling.

Doubling means that one of the notes of the triad is in two voices at the same time (that is, doubled). The G major triad below is rewritten for four parts, with the root G in the Bass and again in the Alto. In other words, the note G is doubled:

G major chord with doubled ‘G’

The doubled note can go to any of the four voices as long as it is within range.

How do you know which note you should double?

As you advance in your learning, you’ll be able to use a variety of options but the easiest rule to start with is this:

Double the primary notes of the scale you’re in.

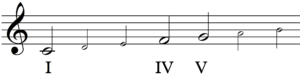

The primary notes (also known as the tonal degrees) are the 1st, 4th and 5th notes of the scale.

For example in C major, the tonal degrees are the notes C (the first), F (the fourth) and G (the fifth). These notes are important as they support the tonic (they help establish and maintain the tonal centre).

The tonal degrees (I, IV and V) in C major

Now here are all the triads of the G major scale. Notice that there is at least one tonal degree in every chord of the scale. No matter the triad, you’ll always find a tonal degree to double!

The triads of C major.

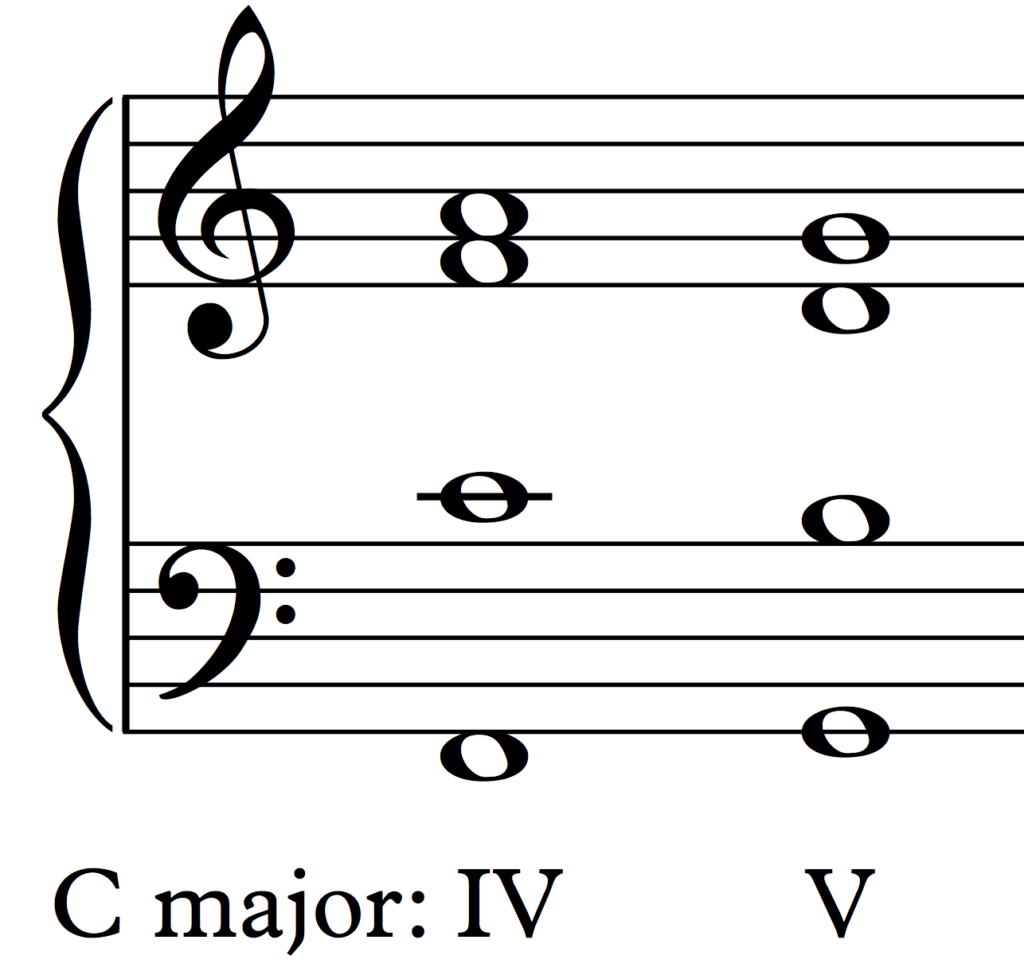

The tonic and subdominant chords themselves (the first and the fourth chords) each contain two tonal degrees. Most often, we double the root of these chords but the alternative is fine too.

Chords IV and V in C major, both with their roots doubled.

Notice that all chord-factors (root, third and fifth) are in the chord. In four-part writing, we can sometimes leave out the 5th of a chord but never leave out the 3rd (as that’s where the chord gets its major or minor sound).

Four-Part Harmony Spacing

Spacing refers to how we distribute the notes of the chord amongst the four parts. Questions such as: “Which note should go on top?”, “How far should the notes be?” and “Where can the 5th of the chord go?” are all a matter of a spacing.

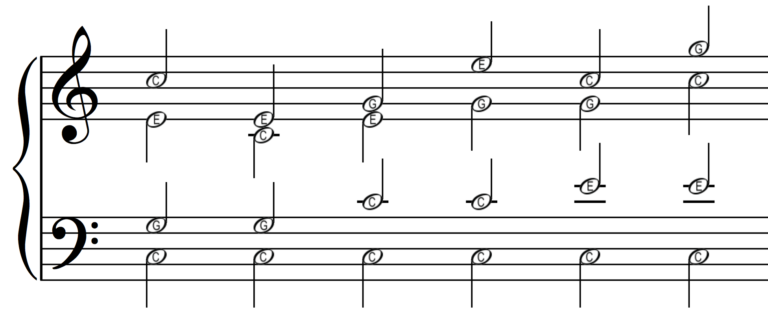

Here are 6 examples of the C major chord in a variety of possible spacings. These chords are all correctly written for four parts but since the notes are arranged in different ways, they all sound different. Observe that all versions are in root position (with the root in the bass), with the root doubled and always within the voices’ proper ranges.

Isn’t it amazing how many ways there are of writing the same chord for 4 parts?

6 versions of the C major chord arranged for 4 parts

In these examples, some intervals are placed close together while some others are wide apart. When the three upper voices (Soprano, Alto and Tenor) are within the span of one octave, they are in what is called Close position. When the tenor and the soprano are further apart than an octave, the chord is in Open position.

Out of the 8 chords of the example above, the chords 2, 3, 5 and 7 are in close position; the chords 1, 4, 6 and 8 are in open position.

One Caution

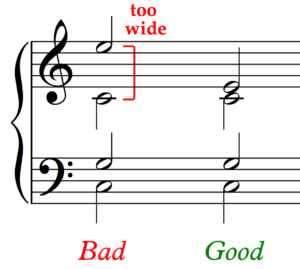

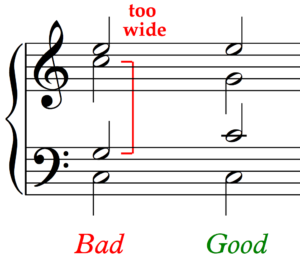

The largest distance between Soprano and Alto shouldn’t be more than a perfect octave. A wide interval between these voices leaves an empty space in the middle. Composers of the 18th and 19th centuries tended to avoid this.

Comparing good and bad spacing between the soprano and alto voices.

For the same reasons, the largest distance between Alto and Tenor is also that of a perfect octave.

Comparing good and bad spacing between the alto and tenor voices.

This doesn’t apply to the interval between the tenor and the bass voices. Here it can be wider than an octave apart because the bass is resonant enough to support itself.

Four-part Harmony Examples Explained

Now that we know the basic rules, let’s say we have these 4 basic triads in the key of F major that we want to arrange for 4-parts. How do we go about it?

Four basic triads: C major, G minor, D minor and F major – to arrange for four-part harmony.

- First, we decide which notes we should double. As we said, we double one of the tonal degrees (the 1st, 4th and 5th notes) of the scale we’re in. In this case, we’re in the key of F major so the tonal degrees are F, B flat and C.

- Next, we have to think about arranging the 4 notes for the 4 voices. Start with the bass notes first.

- Finally, we distribute the rest of the notes amongst the upper 3 voices. With this step we must keep in mind the rest of the rules:

- Notation (2 staves: the top one for Soprano and Alto with stems going up and the bottom one for Tenor and Bass with stems going down);

- Stay within the range of every voice;

- Spacing: keep the Soprano and Alto voices within the span of one octave and the same goes for the Alto and Tenor voices.

Just for practice, here are 2 answers (2 versions) for each chord.

The chords: C major, G minor, D minor and F major arranged for four-part harmony.

Back to Bach

Remember that example by Bach from earlier? Now that we learned a good few things about 4-part writing, let’s have another look and see what else we can learn from the music.

In these 2 bars, we can observe everything we learned so far (and much, much more, of course). We can see how:

- The notation is clear: we have 2 staves each one with 2 voices and the right direction of the stems;

- Every voice sticks to its range;

- Every chord has a tonal degree doubled (since we’re in G major, the tonal degrees are G, C, and D);

- The spacing of the chords is varied: some chords are in open position and others are in close position;

- As we’ve seen at the beginning of this lesson, the 4 voices maintain a more or less independent melodic line but they’re held together by the same chord progression.

Bach Chorale: Gottes Sohn is kommen, BWV 318

Common Questions about Four-Part Harmony

Now that I know the basics of 4-part harmony, what should I learn next? Once you master the basics we’ve talked about in this lesson, the next step is voice leading. This is another essential topic in harmony and it will teach you how the notes of any one chord can (or should) move to the notes of the next chord.

Where can I use 4-part harmony? Well, four-part harmony is everywhere. Nowadays the traditional type is still used in hymns and arrangements for choir but variations of it are used even more. For example, composers of contemporary classical music and jazz musicians often use some sort of 4-part harmony – they just inject new principles to obtain a fresher, more modern sound. Pop, rock and electronic musicians also make use of 4-part harmony when, for example, there is a lead singer or lead guitar with a 3-part backing vocals or keyboards.

As we mentioned earlier, the orchestral instruments are often treated as 4-part choirs too. The strings, we said, are divided into 1st violins, 2nd violins, violas and violoncellos plus double basses. Same idea goes for the orchestral wind instruments: flute on top, then the oboe, then the clarinet and the bassoon at the bottom. Orchestral music and arrangements doesn’t necessarily mean classical music either – film music and all kinds of genres make use of the orchestra.

But perhaps, the strongest argument in favor of learning 4-part harmony is that it teaches you how music works. Chord progressions, melody writing, bass lines, counterpoint, rhythm, texture and a lot more are all part of the study of 4-part harmony. In addition, having any other number of parts than 4 doesn’t really change that much. The basic principles are more or less the same. Once learned, we can apply these principles anywhere and in any way we like.

What is Tonality in Music? And Why does it Matter?

The concept of ‘tonality’ or ‘tonal music’ has wide and far-reaching effects in music but it’s not always understood well. Today we’re going to clarify what the concept really is and what it means for you as a composer or a songwriter.

So what is tonality in music? Tonality (also known as ‘tonal music’) is music that has a tonic – that specific note on which music is the most stable and at rest. In general, tonal music works by establishing a tonic, moving away from it and then returning to it.

Having a tonic is a simple concept but it affects the way we understand music as we hear it, it affects its sense of direction, and it affects the musical structure too. Let’s dive right into this concept with some examples.

Examples of Tonal Music

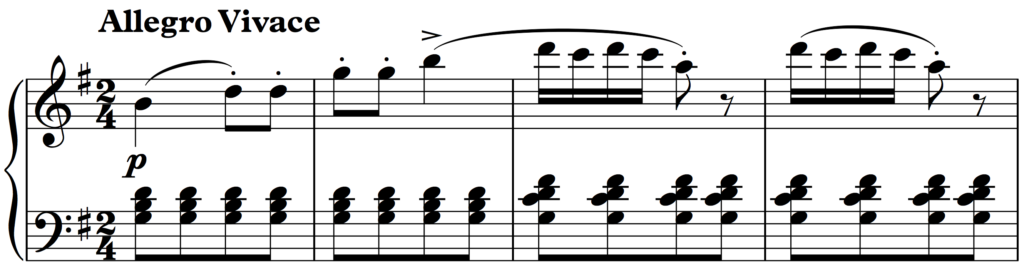

The easiest way to understand what tonal music really means is to listen and, whenever possible, follow the score. Here are 2 melodies from Beethoven – the second one is pretty much the same except for a slight change at the end. Which one of the two gives you the impression that the music has finished?

Phrase 1:

Beethoven: Rondo a Capriccio Op. 129 (a phrase)

Phrase 2:

Beethoven: Rondo a Capriccio Op. 129 (another phrase)

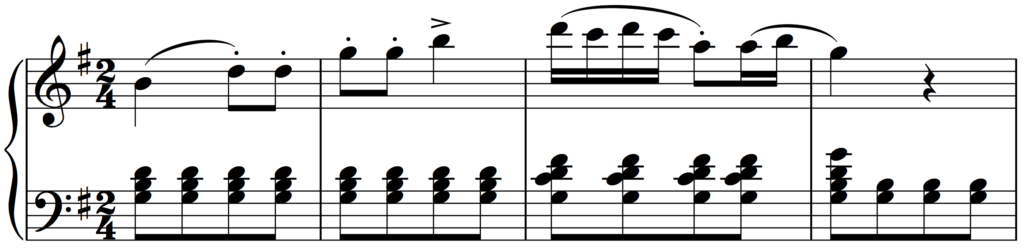

We’ll get to the answer in a second but here’s another similar question, this time with melodies by Haydn. Which one of them gives you a sense that the music has ended?

This one:

Haydn: Sonata in D major (a phrase)

or this one?

Haydn: Sonata in D major (another phrase)

In both questions, the answer is the second phrase and the reason is that they finished on the tonic. If you didn’t hear it this way the first time around, go back and listen again.

What is the Tonic?

The tonic, also known as the tonal centre, is that particular note (and the chord built on it) on which the music is stable and at rest – it feels like home. Melodies and chord progressions are pulled towards it so no matter what happens throughout a piece or a song, the music tends to come back to it. Typically, music in this style begins on the tonic, wanders off for some time and eventually returns to the tonic.

It’s really easy to demonstrate the effect of the tonic for yourself. Pick up any instrument or use an online keyboard and play the C major scale up to the 7th note. Leave it hanging there on the note B.

How do you feel about it ending there?

C major scale without final tonic.

Doesn’t that feel incomplete? Don’t you feel like you want it to go up by one more note? Like this:

C major scale with final tonic.

That final note is the tonic. And that is the psychological effect it has on us. It has a kind of gravitational pull that attracts every melody and chord progression towards it. Leaving the scale hanging on that 7th note creates a tension that resolves only when it finally moves to the tonic. In this sense, the tonic is like a sigh of relief, like coming home and sitting down after a long day at school or at work.

The Tonal Centre and the Major-minor Key System

Having a tonic normally means that the music is based on a major or minor scale. As you know from music theory, a scale is a set of notes with a specific pattern of half steps and whole steps. The major scale, for example, is a 7-note scale with a pattern of 2 whole steps, 1 half step, 3 whole steps and 1 half step. That pattern can start on any note and it will create different major scales. Composers use scales as the main resources for melodies and chords.

Here are the scales of G major and F major. The note F sharp in G major and the note B flat in F major must be introduced so that the pattern of whole steps and half steps is preserved.

G major scale

F major scale

Notice how the tonic note of the scale gives it its name. The G major scale is a major scale whose tonic is G. The F major scale is a major scale whose tonic is F. So the tonic really is all-important and music revolves around it. That’s why it makes sense to know the tonic also as the ‘tonal centre’.

Now the real beauty and power of the major-minor scale system is in how it allows the composer to manipulate the listener’s expectation for the tonic. We learn the details of this topic in harmony but let’s demonstrate what it means using the opening four bars of Beethoven’s 6th symphony:

Beethoven: 6th Symphony theme of the first movement

Clearly, Beethoven had all twelve notes of the musical alphabet to choose from but he chose to use just 7 – the ones that make up the F major scale, in fact. OK that’s easy enough to spot, the music is in F major.

But if we look closer at the music we will see that out of these seven notes, there seem to be two – the F and the C – that are more important than the others. These notes are the only two that Beethoven wrote in the bass and they are significant because they are very long comparing to the short notes of the melody on top.

What makes these two notes even more important is that this little four-bar theme begins and ends on them. It begins on the tonic chord and ends on the dominant chord (that’s the fifth chord of the scale).

Tonic (I) and dominant (V) in F major

Beethoven: 6th Symphony theme uses just I and V

We know why the tonic is crucial – it’s where the scale begins and ends, it’s home and it’s fundamental; But what’s so special about the dominant? To answer this question, we need to focus our attention to ‘Functional Harmony.’

Tonality and Functional Harmony

In tonal music, the dominant chord is just as important as the tonic because it’s the chord that makes us want the tonic. Even if we’re not aware of it, hearing the dominant chord makes us expect its tonic. Here we don’t have the time to get into all the psychoacoustic science behind why this is so, but let me just prove it to you with a very simple example.

In just these 2 bars, listen to how the sound of the dominant chord creates the expectation of the tonic. Notice that when the tonic finally arrives, there is a sense of relief – a feeling of resolution. (In this extract we are in E flat which consists of E flat – F – G – A flat – B flat – C and D).

Schubert: String Quartet no. 10 in E flat major, 2nd movement

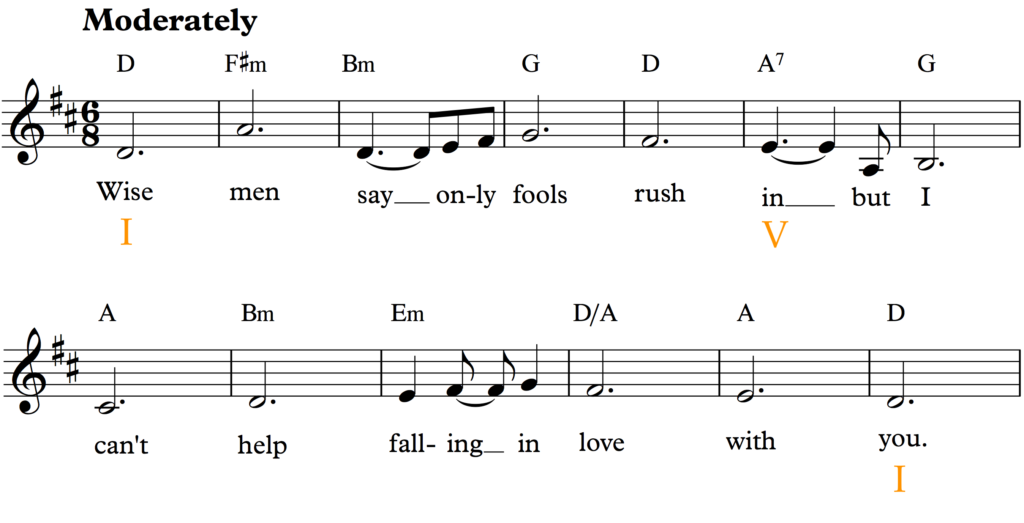

This doesn’t happen only in Classical music. It happens in any music that uses the traditional major and minor scales. Here’s an example from Elvis Presley’s Can’t Help Falling In Love. This phrase is constructed in 2 parts:

The first part (with the lyrics “Wise men say only fools rush in”) begins on the tonic chord and moves to the dominant. The next part (with the lyrics “But I can’t help falling in love with you” continues where the first leaves off and eventually ends on the tonic bringing the line to a satisfactory conclusion.

Elvis Presley: Can’t Help Falling in Love With You – tonic to dominant and back to tonic

By ending the first phrase on the dominant, it invites a continuation. If it ended on the tonic, it would be complete by itself. The melody would be over too quickly!

In tonal music this is known as functional harmony. It’s this strategic use of tonic, dominant and other chords to create expectations and resolving them when appropriate. Functional harmony determines how we experience this music and it explains the logic behind what we hear.

The same thing happens in the Beethoven theme we’ve just been looking at. Why does the theme end on the dominant? Because Beethoven is telling us “Hey, stay tuned… there’s a lot more coming!” With the theme ending on the dominant, we expect to hear the tonic. That is what happens, in fact, but obviously the composer expands that tonic into the full first movement with as much drama as a Shakespeare play or a James Bond movie.

By using the scale of F major in that simple 4-bar theme, Beethoven at once tells us that F is the tonic and that more is coming!

This is the power of tonality within the major/minor system and functional harmony – it establishes a tonic, creates the ‘story’ by leaving it so that eventually we can return to a resolution on the tonic.

Tonality and the Sense of Musical Direction

So our picture of tonality is now getting clearer: tonal music is music that has a tonic and it normally works within the major/minor keys system and functional harmony. Our exploration of tonality cannot stop here, however, because there are two more fundamental elements that it influences.

It’s the sense of direction and structure in music.

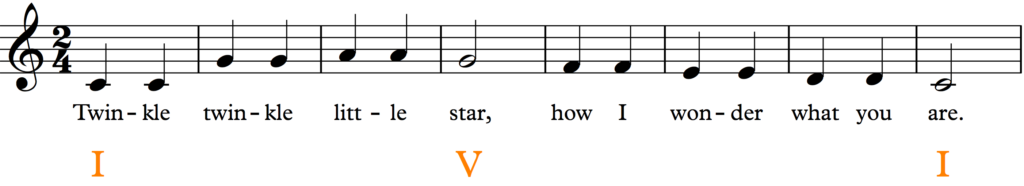

Since music comes out of the tonic only to eventually return to it, then it means that the process of leaving and returning to tonic creates a sense of direction – an expectation that the music is, at some point, returning to that tonic just like we heard in the examples throughout this lesson.

This sense of coming and going to tonic can be heard everywhere. Consider the simple tune to Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. Starting out on tonic C, the melody skips to G and stays there after a brief visit to its neighbour note A. It then simply returns to end on C descending one step a time through F, E and D. In other words, leaving the tonic and then coming back to it is what guides the melody all along.

Twinkle, twinkle little star

Even in a simple children’s tune, we can see tonality in practice. What is really fascinating is that tonal music makes sense simply because it’s guided by these principles. Listeners don’t have to be aware of any of this to enjoy the music.

Tonality and Form

In the example from Beethoven’s 6th symphony theme, we hear that there is something very satisfying with the melody ending on those particular notes at the fourth bar. It sounds like the destination of everything that’s happened before (bars 1 to 3) was this chord all along. In other words, the music has a strong sense of direction – with a clear arrival at this musical goal.

As listeners, we do perceive music in terms of these musical goals. Once a musical goal is reached, we expect that the journey towards the next one begins and so on and so forth we experience the music in chunks or in sections.

As we saw already, this is what creates the musical journey within a tonal composition – we leave tonic and return to it. On our way back to tonic, we might experience some ups and downs, some detours, some surprises and some tension (it all depends on the composer’s style and intentions) but eventually the drama resolves and the journey ends firmly on tonic.

This is how the musical forms of the baroque, classical and romantic periods works. In the sonata form, for example, we get one or more themes based on the tonic key (the principal key), then we get one or more contrasting themes in the dominant key. This is followed by the development section in which the music travels to a variety of keys using bits and pieces of those themes we heard at the beginning. The whole thing then finishes with a return to the tonic.

A similar idea is in the earlier dance music of the baroque style. We get a first section based on the tonic and a second section based on the dominant. The musical material of the second section could be very similar to that of the first because the change of key or ‘tonality’ (known as modulation) is enough of a contrast.

Tonality and Consonance vs. Dissonance

So far we’ve learned that tonal music works by establishing a tonic, leaving the tonic and then returning to it. But how is the tonic established in the first place? And what does it actually mean to return to it?

The answer is in the concept of consonance and dissonance.

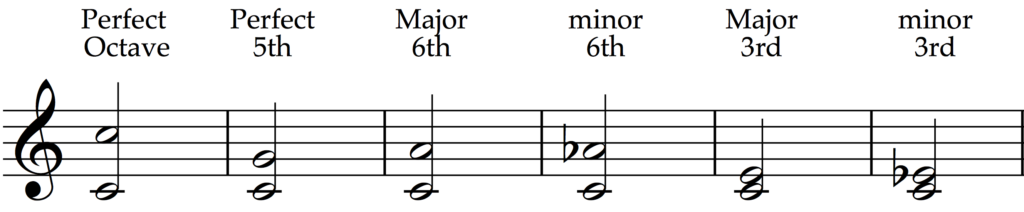

These terms refer to the level of tension inherent in any musical sound: from no tension at all to lots of it. Consonant intervals are pairs of notes that don’t have tension (they’re stable) and dissonant intervals are those that do have tension (they’re unstable).

Consonant intervals:

Consonant intervals

Dissonant intervals:

Whether the perfect fourth is consonant or dissonant usually depends on context. The same goes for the diminished fifth (or augmented fourth) but typically, it’s considered a dissonance.

In tonal music, dissonance carries a certain energy that looks forward towards a resolution into consonance. Dissonance is unstable and it resolves into consonance, which is stable. The simplest and most important example of this is once again with the tonic and dominant polarities.

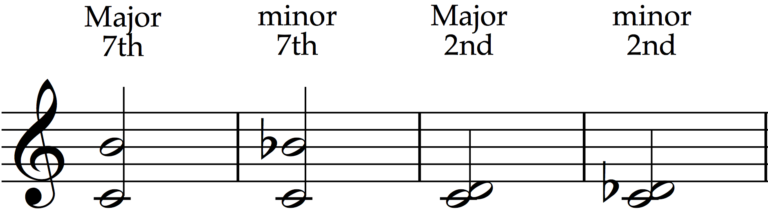

Here is the dominant 7th chord of C major consisting of the notes G – B – D – F. That top F (the 7th) creates two dissonances. One with the note G (the root of the chord) and the other with the note B (the third of the chord).

① = minor 7th

② = diminished 5th

A dominant 7th chord consisting of a minor 7th and a diminished 5th above the root.

Since this chord is dissonant, it requires a resolution into a consonance. By far, the most typical resolution of the unstable dominant 7th is into the stable tonic. The root G jumps to C, the third B moves a step up (just like it does in the ascending major scale), and the 7th F typically moves a step down to E (the third of the tonic). This is how the dissonance is normally controlled and resolved in tonal music.

V7 to I resolution in C major

This simple progression, which moves from dissonance to consonance, is one of the quickest ways of establishing or returning to the tonic. It’s no wonder that, as we’ve seen today, this is one of the most common in all of tonal music.

Common Questions about Tonality in Music

Is ‘tonality’ the same as ‘key’? The concept of tonality refers to music that works around a tonic. The term ‘key’ refers to the particular set of notes (the scale) on which any piece or section of music is based. But since the terms are so closely related, they are sometimes interchangeable. In a statement such as: “The tonality of this piece is F major”, ‘tonality’ is the same as ‘key’.

Is there music that isn’t tonal, music that doesn’t have a tonic? Yes, there are several other systems. Some are older than tonality and others were developed in the 20th century. Examples include atonal music, bitonal music, polytonal music, and pandiatonicism.

What is the difference between harmony and tonality? Tonality refers to music that has a tonic while harmony is the study of chords and chord progressions. Harmony is often tonal (with chord progressions based on the major and minor scales) but it can be of other types too.