MUSIC THEORY ( TIME )

1.2. Time

Duration: Note Lengths in Written Music*

The Shape of a Note

In standard notation, a single musical sound is written as a note. The two most important things a written piece of music needs to tell you about a note are its pitch – how high or low it is – and its duration – how long it lasts.

To find out the pitch of a written note, you look at the clef and the key signature, then see what line or space the note is on. The higher a note sits on the staff, the higher it sounds. To find out the duration of the written note, you look at the tempo and the time signature and then see what the note looks like.

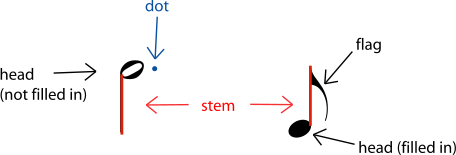

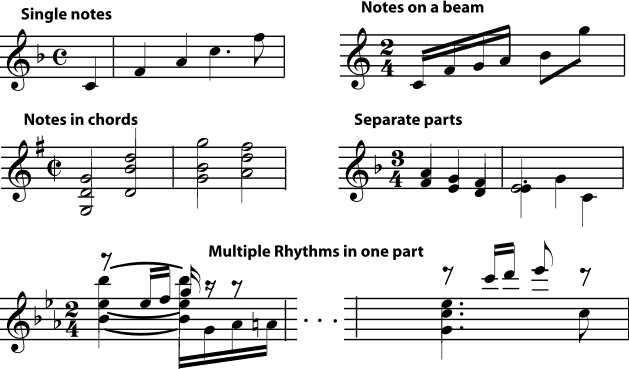

Figure 1.43. The Parts of a Note

All of the parts of a written note affect how long it lasts.

The pitch of the note depends only on what line or space the head of the note is on. (Please see pitch , clef and key signature for more information.) If the note does not have a head (see Figure 1.44), that means that it does not have one definite pitch.

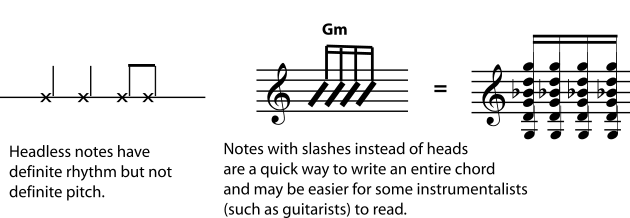

Figure 1.44. Notes Without Heads

If a note does not have head, it does not have one definite pitch. Such a note may be a pitchless sound, like a drum beat or a hand clap, or it may be an entire chord rather than a single note.

The head of the note may be filled in (black), or not. The note may also have (or not) a stem, one or more flags, beams connecting it to other notes, or one or more dots following the head of the note. All of these things affect how much time the note is given in the music.Note

A dot that is someplace other than next to the head of the note does not affect the rhythm. Other dots are articulation marks. They may affect the actual length of the note (the amount of time it sounds), but do not affect the amount of time it must be given. (The extra time when the note could be sounding, but isn’t, becomes an unwritten rest.) If this is confusing, please see the explanation in articulation.

The Length of a Note

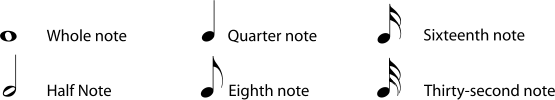

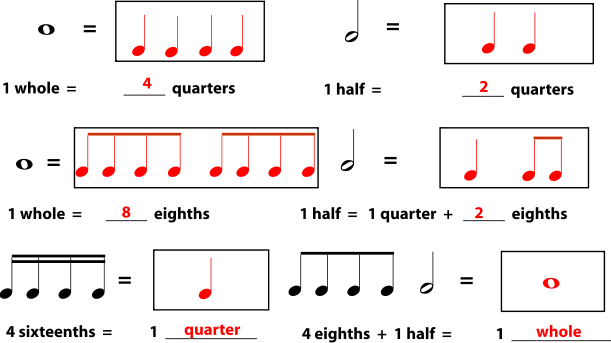

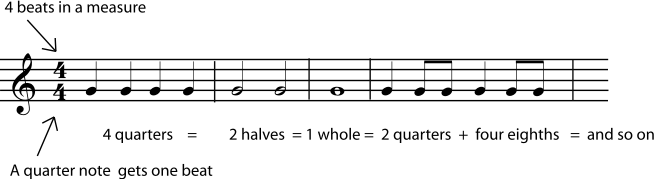

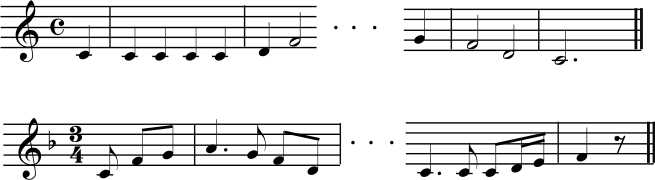

Figure 1.45. Most Common Note Lengths

The simplest-looking note, with no stems or flags, is a whole note. All other note lengths are defined by how long they last compared to a whole note. A note that lasts half as long as a whole note is a half note. A note that lasts a quarter as long as a whole note is a quarter note. The pattern continues with eighth notes, sixteenth notes, thirty-second notes, sixty-fourth notes, and so on, each type of note being half the length of the previous type. (There are no such thing as third notes, sixth notes, tenth notes, etc.; see Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions to find out how notes of unusual lengths are written.)

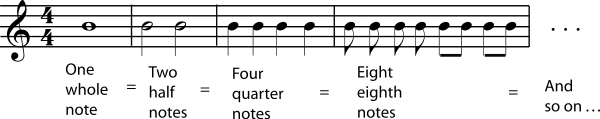

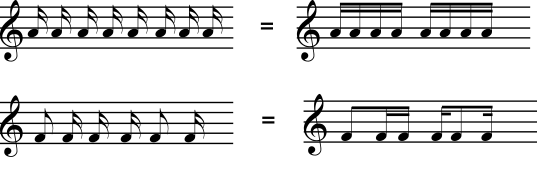

Figure 1.46.

Note lengths work just like fractions in arithmetic: two half notes or four quarter notes last the same amount of time as one whole note. Flags are often replaced by beams that connect the notes into easy-to-read groups.

You may have noticed that some of the eighth notes in Figure 1.46 don’t have flags; instead they have a beam connecting them to another eighth note. If flagged notes are next to each other, their flags can be replaced by beams that connect the notes into easy-to-read groups. The beams may connect notes that are all in the same beat, or, in some vocal music, they may connect notes that are sung on the same text syllable. Each note will have the same number of beams as it would have flags.

Figure 1.47. Notes with Beams

The notes connected with beams are easier to read quickly than the flagged notes. Notice that each note has the same number of beams as it would have flags, even if it is connected to a different type of note. The notes are often (but not always) connected so that each beamed group gets one beat. This makes the notes easier to read quickly.

You may have also noticed that the note lengths sound like fractions in arithmetic. In fact they work very much like fractions: two half notes will be equal to (last as long as) one whole note; four eighth notes will be the same length as one half note; and so on. (For classroom activities relating music to fractions, see Fractions, Multiples, Beats, and Measures.)

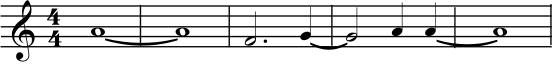

Example 1.2.

Figure 1.48.

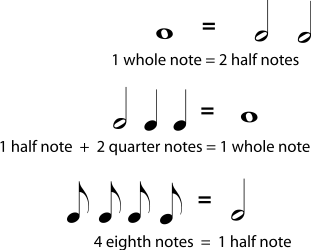

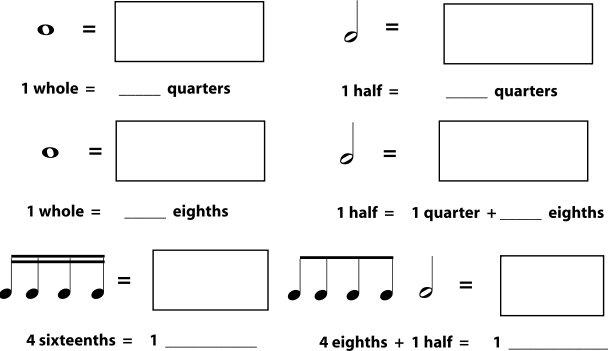

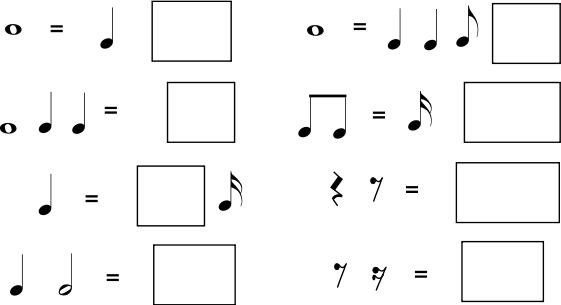

Exercise 1.6.1.

Draw the missing notes and fill in the blanks to make each side the same duration (length of time).

Figure 1.49.

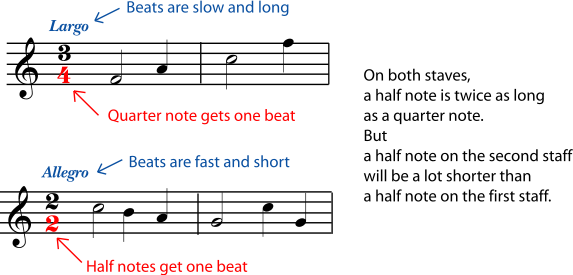

So how long does each of these notes actually last? That depends on a couple of things. A written note lasts for a certain amount of time measured in beats. To find out exactly how many beats it takes, you must know the time signature. And to find out how long a beat is, you need to know the tempo.

Example 1.3.

Figure 1.50.

In any particular section of a piece of music, a half note is always twice as long as a quarter note. But how long each note actually lasts depends on the time signature and the tempo.

More about Stems

Whether a stem points up or down does not affect the note length at all. There are two basic ideas that lead to the rules for stem direction. One is that the music should be as easy as possible to read and understand. The other is that the notes should tend to be “in the staff” as much as reasonably possible.

Basic Stem Direction Rules

- Single Notes – Notes below the middle line of the staff should be stem up. Notes on or above the middle line should be stem down.

- Notes sharing a stem (block chords) – Generally, the stem direction will be the direction for the note that is furthest away from the middle line of the staff

- Notes sharing a beam – Again, generally you will want to use the stem direction of the note farthest from the center of the staff, to keep the beam near the staff.

- Different rhythms being played at the same time by the same player – Clarity requires that you write one rhythm with stems up and the other stems down.

- Two parts for different performers written on the same staff – If the parts have the same rhythm, they may be written as block chords. If they do not, the stems for one part (the “high” part or “first” part) will point up and the stems for the other part will point down. This rule is especially important when the two parts cross; otherwise there is no way for the performers to know that the “low” part should be reading the high note at that spot.

Figure 1.51. Stem Direction

Keep stems and beams in or near the staff, but also use stem direction to clarify rhythms and parts when necessary.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.6.1.

Figure 1.52.

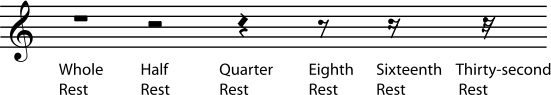

Duration: Rest Length*

A rest stands for a silence in music. For each kind of note, there is a written rest of the same length.

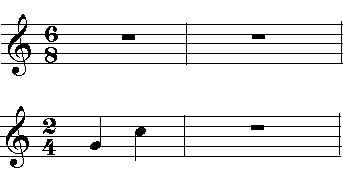

Figure 1.53. The Most Common Rests

Exercise 1.7.1.

For each note on the first line, write a rest of the same length on the second line. The first measure is done for you.

Figure 1.54.

Rests don’t necessarily mean that there is silence in the music at that point; only that that part is silent. Often, on a staff with multiple parts, a rest must be used as a placeholder for one of the parts, even if a single person is playing both parts. When the rhythms are complex, this is necessary to make the rhythm in each part clear.

Figure 1.55.

When multiple simultaneous rhythms are written on the same staff, rests may be used to clarify individual rhythms, even if another rhythm contains notes at that point.

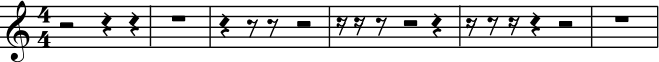

The normal rule in common notation is that, for any line of music, the notes and rests in each measure must “add up” to exactly the amount in the time signature, no more and no less. For example, in 3/4 time, a measure can have any combination of notes and rests that is the same length as three quarter notes. There is only one common exception to this rule. As a simplifying shorthand, a completely silent measure can simply have a whole rest. In this case, “whole rest” does not necessarily mean “rest for the same length of time as a whole note”; it means “rest for the entire measure”.

Figure 1.56.

A whole rest may be used to indicate a completely silent measure, no matter what the actual length of the measure will be.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.7.1.

Figure 1.57.

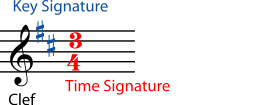

Time Signature*

The time signature appears at the beginning of a piece of music, right after the key signature. Unlike the key signature, which is on every staff, the time signature will not appear again in the music unless the meter changes. The meter of a piece of music is its basic rhythm; the time signature is the symbol that tells you the meter of the piece and how (with what type of note) it is written.

Figure 1.58.

The time signature appears at the beginning of the piece of music, right after the clef symbol and key signature.

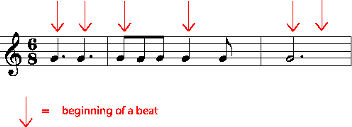

Beats and Measures

Because music is heard over a period of time, one of the main ways music is organized is by dividing that time up into short periods called beats. In most music, things tend to happen right at the beginning of each beat. This makes the beat easy to hear and feel. When you clap your hands, tap your toes, or dance, you are “moving to the beat”. Your claps are sounding at the beginning of the beat, too. This is also called being “on the downbeat”, because it is the time when the conductor’s baton hits the bottom of its path and starts moving up again.

Example 1.4.

Listen to excerpts A, B, C and D. Can you clap your hands, tap your feet, or otherwise move “to the beat”? Can you feel the 1-2-1-2 or 1-2-3-1-2-3 of the meter? Is there a piece in which it is easier or harder to feel the beat?

- A

- B

- C

- D

The downbeat is the strongest part of the beat, but some downbeats are stronger than others. Usually a pattern can be heard in the beats: strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak, or strong-weak-strong-weak. So beats are organized even further by grouping them into bars, or measures. (The two words mean the same thing.) For example, for music with a beat pattern of strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak, or 1-2-3-1-2-3, a measure would have three beats in it. The time signature tells you two things: how many beats there are in each measure, and what type of note gets a beat.

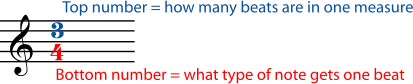

Figure 1.59. Reading the Time Signature

This time signature means that there are three quarter notes (or any combination of notes that equals three quarter notes) in every measure. A piece with this time signature would be “in three four time” or just “in three four”.

Exercise 1.8.1.

Listen again to the music in Example 1.4. Instead of clapping, count each beat. Decide whether the music has 2, 3, or 4 beats per measure. In other words, does it feel more natural to count 1-2-1-2, 1-2-3-1-2-3, or 1-2-3-4-1-2-3-4?

Meter: Reading Time Signatures

Most time signatures contain two numbers. The top number tells you how many beats there are in a measure. The bottom number tells you what kind of note gets a beat.

Figure 1.60.

In “four four” time, there are four beats in a measure and a quarter note gets a beat. Any combination of notes that equals four quarters can be used to fill up a measure.

You may have noticed that the time signature looks a little like a fraction in arithmetic. Filling up measures feels a little like finding equivalent fractions, too. In “four four time”, for example, there are four beats in a measure and a quarter note gets one beat. So four quarter notes would fill up one measure. But so would any other combination of notes that equals four quarters: one whole, two halves, one half plus two quarters, and so on.

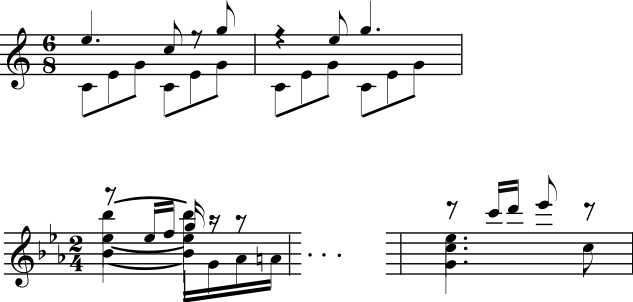

Example 1.5.

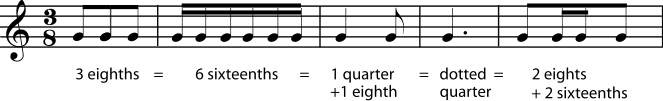

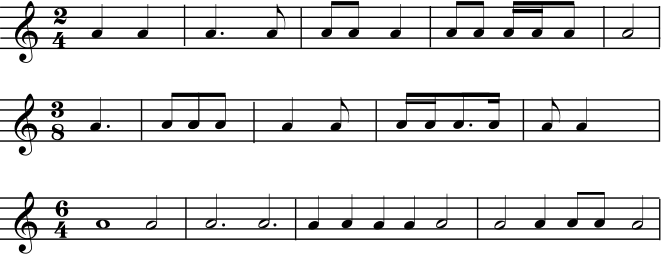

If the time signature is three eight, any combination of notes that adds up to three eighths will fill a measure. Remember that a dot is worth an extra half of the note it follows. Listen to the rhythms in Figure 1.61.

Figure 1.61.

If the time signature is three eight, a measure may be filled with any combination of notes and rests that adds up to three eight.

Exercise 1.8.2.

Write each of the time signatures below (with a clef symbol) at the beginning of a staff. Write at least four measures of music in each time signature. Fill each measure with a different combination of note lengths. Use at least one dotted note on each staff. If you need some staff paper, you can download this PDF file.

- Two four time

- Three eight time

- Six four time

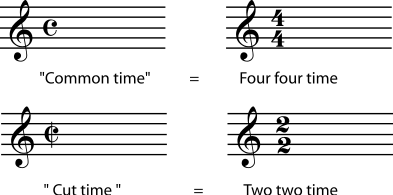

A few time signatures don’t have to be written as numbers. Four four time is used so much that it is often called common time, written as a bold “C”. When both fours are “cut” in half to twos, you have cut time, written as a “C” cut by a vertical slash.

Figure 1.62.

Counting and Conducting

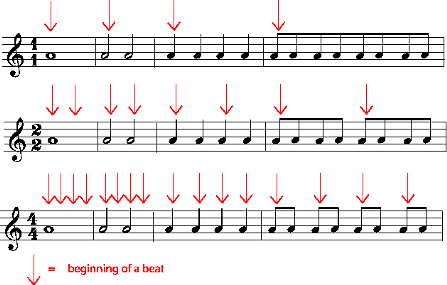

You may have already noticed that a measure in four four time looks the same as a measure in two two. After all, in arithmetic, four quarters adds up to the same thing as two halves. For that matter, why not call the time signature “one one” or “eight eight”?

Figure 1.63.

Measures in all of these meters look the same, but feel different. The difference is how many downbeats there are in a measure.

Or why not write two two as two four, giving quarter notes the beat instead of half notes? The music would look very different, but it would sound the same, as long as you made the beats the same speed. The music in each of the staves in Figure 1.64 would sound like this.

Figure 1.64.

The music in each of these staves should sound exactly alike.

So why is one time signature chosen rather than another? The composer will normally choose a time signature that makes the music easy to read and also easy to count and conduct. Does the music feel like it has four beats in every measure, or does it go by so quickly that you only have time to tap your foot twice in a measure?

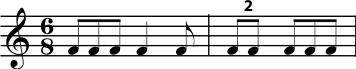

A common exception to this is six eight time, and the other time signatures (for example nine eight and twelve eight) commonly used to write compound meters. A piece in six eight might have six beats in every measure, with an eighth note getting a beat. But it is more likely that the conductor will give only two beats per measure, with a dotted quarter (or three eighth notes) getting one beat. Since beats normally get divided into halves and quarters, this is the easiest way for composers to write beats that are divided into thirds. In the same way, three eight may only have one beat per measure; nine eight, three beats per measure; and twelve eight, four beats per measure.

Figure 1.65.

In six eight time, a dotted quarter usually gets one beat. This is the easiest way to write beats that are evenly divided into three rather than two.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.8.1.

- A has a very strong, quick 1-2-3 beat.

- B is in a slow (easy) 2. You may feel it in a fast 4.

- C is in a stately 4.

- D is in 3, but the beat may be harder to feel than in A because the rhythms are more complex and the performer is taking some liberties with the tempo.

Solution to Exercise 1.8.2.

There are an enormous number of possible note combinations for any time signature. That’s one of the things that makes music interesting. Here are some possibilities. If you are not sure that yours are correct, check with your music instructor.

Figure 1.66.

These are only a few of the many, many possible note combinations that could be used in these time signatures.

Meter*

What is Meter?

The meter of a piece of music is the arrangment of its rhythms in a repetitive pattern of strong and weak beats. This does not necessarily mean that the rhythms themselves are repetitive, but they do strongly suggest a repeated pattern of pulses. It is on these pulses, the beat of the music, that you tap your foot, clap your hands, dance, etc.

Some music does not have a meter. Ancient music, such as Gregorian chants; new music, such as some experimental twentieth-century art music; and Non-Western music, such as some native American flute music, may not have a strong, repetitive pattern of beats. Other types of music, such as traditional Western African drumming, may have very complex meters that can be difficult for the beginner to identify.

But most Western music has simple, repetitive patterns of beats. This makes meter a very useful way to organize the music. Common notation, for example, divides the written music into small groups of beats called measures, or bars. The lines dividing each measure from the next help the musician reading the music to keep track of the rhythms. A piece (or section of the piece) is assigned a time signature that tells the performer how many beats to expect in each measure, and what type of note should get one beat. (For more on reading time signatures, please see Time Signature.)

Conducting also depends on the meter of the piece; conductors use different conducting patterns for the different meters. These patterns emphasize the differences between the stronger and weaker beats to help the performers keep track of where they are in the music.

But the conducting patterns depend only on the pattern of strong and weak beats. In other words, they only depend on “how many beats there are in a measure”, not “what type of note gets a beat”. So even though the time signature is often called the “meter” of a piece, one can talk about meter without worrying about the time signature or even being able to read music. (Teachers, note that this means that children can be introduced to the concept of meter long before they are reading music. See Meter Activities for some suggestions.)

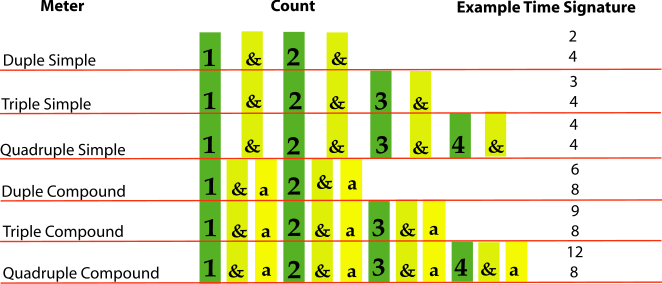

Classifying Meters

Meters can be classified by counting the number of beats from one strong beat to the next. For example, if the meter of the music feels like “strong-weak-strong-weak”, it is in duple meter. “strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak” is triple meter, and “strong-weak-weak-weak” is quadruple. (Most people don’t bother classifying the more unusual meters, such as those with five beats in a measure.)

Meters can also be classified as either simple or compound. In a simple meter, each beat is basically divided into halves. In compound meters, each beat is divided into thirds.

A borrowed division occurs whenever the basic meter of a piece is interrupted by some beats that sound like they are “borrowed” from a different meter. One of the most common examples of this is the use of triplets to add some compound meter to a piece that is mostly in a simple meter. (See Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions to see what borrowed divisions look like in common notation.)

Recognizing Meters

To learn to recognize meter, remember that (in most Western music) the beats and the subdivisions of beats are all equal and even. So you are basically listening for a running, even pulse underlying the rhythms of the music. For example, if it makes sense to count along with the music “ONE-and-Two-and-ONE-and-Two-and” (with all the syllables very evenly spaced) then you probably have a simple duple meter. But if it’s more comfortable to count “ONE-and-a-Two-and-a-ONE-and-a-Two-and-a”, it’s probably compound duple meter. (Make sure numbers always come on a pulse, and “one” always on the strongest pulse.)

This may take some practice if you’re not used to it, but it can be useful practice for anyone who is learning about music. To help you get started, the figure below sums up the most-used meters. To help give you an idea of what each meter should feel like, here are some animations (with sound) of duple simple, duple compound, triple simple, triple compound, quadruple simple, and quadruple compound meters. You may also want to listen to some examples of music that is in simple duple, simple triple, simple quadruple, compound duple, and compound triple meters.

Figure 1.67. Meters

Remember that meter is not the same as time signature; the time signatures given here are just examples. For example, 2/2 and 2/8 are also simple duple meters.

Pickup Notes and Measures*

Pickup Measures

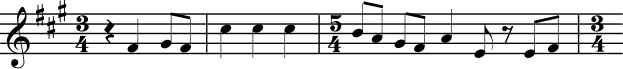

Normally, all the measures of a piece of music must have exactly the number of beats indicated in the time signature. The beats may be filled with any combination of notes or rests (with duration values also dictated by the time signature), but they must combine to make exactly the right number of beats. If a measure or group of measures has more or fewer beats, the time signature must change.

Figure 1.68.

Normally, a composer who wants to put more or fewer beats in a measure must change the time signature, as in this example from Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov.

There is one common exception to this rule. (There are also some less common exceptions not discussed here.) Often, a piece of music does not begin on the strongest downbeat. Instead, the strong beat that people like to count as “one” (the beginning of a measure), happens on the second or third note, or even later. In this case, the first measure may be a full measure that begins with some rests. But often the first measure is simply not a full measure. This shortened first measure is called a pickup measure.

If there is a pickup measure, the final measure of the piece should be shortened by the length of the pickup measure (although this rule is sometimes ignored in less formal written music). For example, if the meter of the piece has four beats, and the pickup measure has one beat, then the final measure should have only three beats. (Of course, any combination of notes and rests can be used, as long as the total in the first and final measures equals one full measure.

Figure 1.69.

If a piece begins with a pickup measure, the final measure of the piece is shortened by the length of the pickup measure.

Pickup Notes

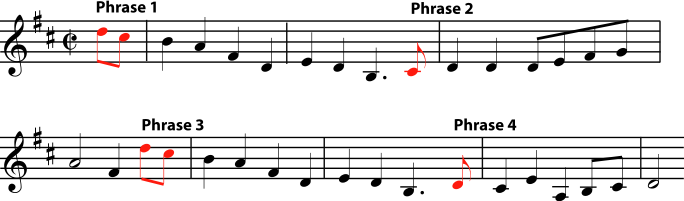

Any phrase of music (not just the first one) may begin someplace other than on a strong downbeat. All the notes before the first strong downbeat of any phrase are the pickup notes to that phrase.

Figure 1.70.

Any phrase may begin with pickup notes. Each of these four phrases begins with one or two pickup notes. (You may listen to the tune here; can you hear that the pickup notes lead to the stronger downbeat?)

A piece that is using pickup measures or pickup notes may also sometimes place a double bar (with or without repeat signs) inside a measure, in order to make it clear which phrase and which section of the music the pickup notes belong to. If this happens (which is a bit rare, because it can be confusing to read), there is still a single bar line where it should be, at the end of the measure.

Figure 1.71.

At the ends of sections of the music, a measure may be interrupted by a double bar that places the pickup notes in the correct section and assures that repeats have the correct number of beats. When this happens, the bar line will still appear at the end of the completed measure. This notation can be confusing, though, and in some music the pickups and repeats are written in a way that avoids these broken-up measures.

Dots, Ties, and Borrowed Divisions*

A half note is half the length of a whole note; a quarter note is half the length of a half note; an eighth note is half the length of a quarter note, and so on. (See Duration:Note Length.) The same goes for rests. (See Duration: Rest Length.) But what if you want a note (or rest) length that isn’t half of another note (or rest) length?

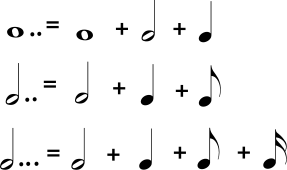

Dotted Notes

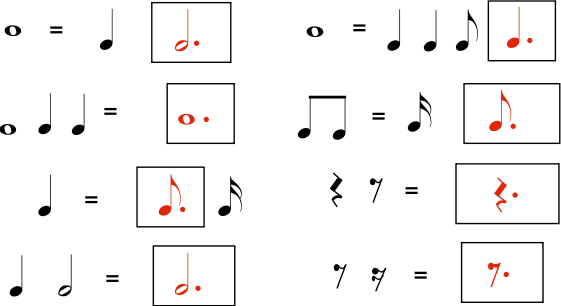

One way to get a different length is by dotting the note or rest. A dotted note is one-and-a-half times the length of the same note without the dot. In other words, the note keeps its original length and adds another half of that original length because of the dot. So a dotted half note, for example, would last as long as a half note plus a quarter note, or three quarters of a whole note.

Figure 1.72.

The dot acts as if it is adding another note half the length of the original note. A dotted quarter note, for example, would be the length of a quarter plus an eighth, because an eighth note is half the length of a quarter note.

Exercise 1.11.1.

Make groups of equal length on each side, by putting a dotted note or rest in the box.

Figure 1.73.

A note may have more than one dot. Each dot adds half the length that the dot before it added. For example, the first dot after a half note adds a quarter note length; the second dot would add an eighth note length.

Figure 1.74.

When a note has more than one dot, each dot is worth half of the dot before it.

Tied Notes

A dotted half lasts as long as a half note plus a quarter note. The same length may be written as a half note and a quarter note tied together. Tied notes are written with a curved line connecting two notes that are on the same line or the same space in the staff. Notes of any length may be tied together, and more than two notes may be tied together. The sound they stand for will be a single note that is the length of all the tied notes added together. This is another way to make a great variety of note lengths. Tied notes are also the only way to write a sound that starts in one measure and ends in a different measure.Note

Ties may look like slurs, but they are not the same; a slur connects to notes with different pitches and is a type of articulation.

Figure 1.75.

When these eight notes are played as written, only five distinct notes are heard: one note the length of two whole notes; then a dotted half note; then another note the same length as the dotted half note; then a quarter note; then a note the same length as a whole note plus a quarter note.

Borrowed Divisions

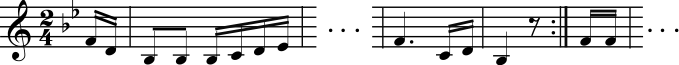

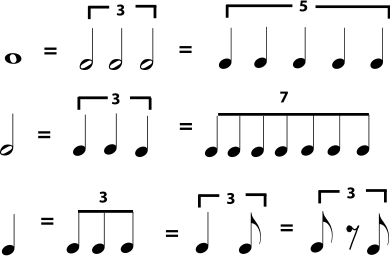

Dots and ties give you much freedom to write notes of varying lengths, but so far you must build your notes from halves of other notes. If you want to divide a note length into anything other than halves or halves of halves – if you want to divide a beat into thirds or fifths, for example – you must write the number of the division over the notes. These unusual subdivisions are called borrowed divisions because they sound as if they have been borrowed from a completely different meter. They can be difficult to perform correctly and are avoided in music for beginners. The only one that is commonly used is triplets, which divide a note length into equal thirds.

Figure 1.76. Some Borrowed Divisions

Any common note length can be divided into an unusual number of equal-length notes and rests, for example by dividing a whole note into three instead of two “half” notes. The notes are labeled with the appropriate number. If there might be any question as to which notes are involved in the borrowed division, a bracket is placed above them. Triplets are by far the most common borrowed division.

Figure 1.77. Borrowed Duplets

In a compound meter, which normally divides a beat into three, the borrowed division may divide the beat into two, as in a simple meter. You may also see duplets in swing music.

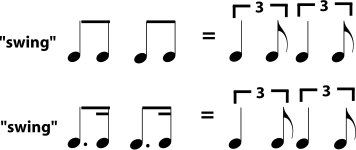

Notes in jazzy-sounding music that has a “swing” beat are often assumed to be triplet rhythms, even when they look like regular divisions; for example, two written eighth notes (or a dotted quarter-sixteenth) might sound like a triplet quarter-eighth rhythm. In jazz and other popular music styles, a tempo notation that says swing usually means that all rhythms should be played as triplets. Straight means to play the rhythms as written.Note

Some jazz musicians prefer to think of a swing rhythm as more of a heavy accent on the second eighth, rather than as a triplet rhythm, particularly when the tempo is fast. This distinction is not important for students of music theory, but jazz students will want to work hard on using both rhythm and articulation to produce a convincing “swing”.

Figure 1.78. Swing Rhythms

Jazz or blues with a “swing” rhythm often assumes that all divisions are triplets. The swung triplets may be written as triplets, or they may simply be written as “straight” eighth notes or dotted eighth-sixteenths. If rhythms are not written as triplets, the tempo marking usually includes an indication to “swing”, or it may simply be implied by the style and genre of the music.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.11.1.

Figure 1.79.

Syncopation*

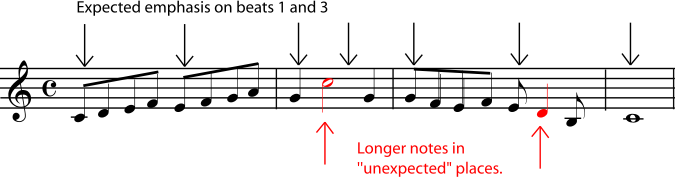

A syncopation or syncopated rhythm is any rhythm that puts an emphasis on a beat, or a subdivision of a beat, that is not usually emphasized. One of the most obvious features of Western music, to be heard in most everything from Bach to blues, is a strong, steady beat that can easily be grouped evenly into measures. (In other words, each measure has the same number of beats, and you can hear the measures in the music because the first beat of the measure is the strongest. See Time Signature and Meter for more on this.) This makes it easy for you to dance or clap your hands to the music. But music that follows the same rhythmic pattern all the time can get pretty boring. Syncopation is one way to liven things up. The music can suddenly emphasize the weaker beats of the measure, or it can even emphasize notes that are not on the beat at all. For example, listen to the melody in Figure 1.80.

Figure 1.80.

A syncopation may involve putting an “important” note on a weak beat, or off the beat altogether.

The first measure clearly establishes a simple quadruple meter (“ONE and two and THREE and four and”), in which important things, like changes in the melody, happen on beat one or three. But then, in the second measure, a syncopation happens; the longest and highest note is on beat two, normally a weak beat. In the syncopation in the third measure, the longest note doesn’t even begin on a beat; it begins half-way through the third beat. (Some musicians would say “on the up-beat” or “on the ‘and’ of three”.) Now listen to another example from a Boccherini minuet. Again, some of the long notes begin half-way between the beats, or “on the up-beat”. Notice, however, that in other places in the music, the melody establishes the meter very strongly, so that the syncopations are easily heard to be syncopations.

Figure 1.81.

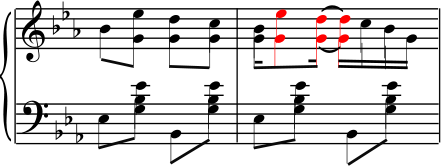

Syncopation is one of the most important elements in ragtime music, as illustrated in this example from Scott Joplin’s Peacherine Rag. Notice that the syncopated notes in the melody come on the second and fourth quarters of the beat, essentially alternating with the strong eighth-note pattern laid down in the accompaniment.

Another way to strongly establish the meter is to have the syncopated rhythm playing in one part of the music while another part plays a more regular rhythm, as in this passage from Scott Joplin (see Figure 1.81). Syncopations can happen anywhere: in the melody, the bass line, the rhythm section, the chordal accompaniment. Any spot in the rhythm that is normally weak (a weak beat, an upbeat, a sixteenth of a beat, a part of a triplet) can be given emphasis by a syncopation. It can suddenly be made important by a long or high note in the melody, a change in direction of the melody, a chord change, or a written accent. Depending on the tempo of the music and the type of syncopation, a syncopated rhythm can make the music sound jaunty, jazzy, unsteady, surprising, uncertain, exciting, or just more interesting.

Figure 1.82.

Syncopation can be added just by putting accents in unexpected places.

Other musical traditions tend to be more rhythmically complex than Western music, and much of the syncopation in modern American music is due to the influence of Non-Western traditions, particularly the African roots of the African-American tradition. Syncopation is such an important aspect of much American music, in fact, that the type of syncopation used in a piece is one of the most important clues to the style and genre of the music. Ragtime, for example, would hardly be ragtime without the jaunty syncopations in the melody set against the steady unsyncopated bass. The “swing” rhythm in big-band jazz and the “back-beat” of many types of rock are also specific types of syncopation. If you want practice hearing syncopations, listen to some ragtime or jazz. Tap your foot to find the beat, and then notice how often important musical “events” are happening “in between” your foot-taps.

Tempo*

The tempo of a piece of music is its speed. There are two ways to specify a tempo. Metronome markings are absolute and specific. Other tempo markings are verbal descriptions which are more relative and subjective. Both types of markings usually appear above the staff, at the beginning of the piece, and then at any spot where the tempo changes. Markings that ask the player to deviate slightly from the main tempo, such as ritardando may appear either above or below the staff.

Metronome Markings

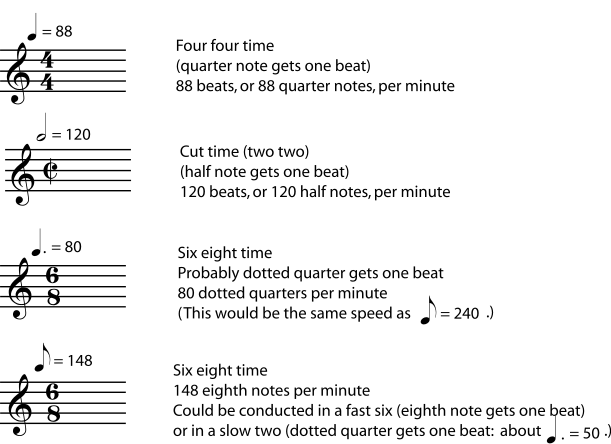

Metronome markings are given in beats per minute. They can be estimated using a clock with a second hand, but the easiest way to find them is with a metronome, which is a tool that can give a beat-per-minute tempo as a clicking sound or a pulse of light. Figure 1.83 shows some examples of metronome markings.

Figure 1.83.

Metronomes often come with other tempo indications written on them, but this is misleading. For example, a metronome may have allegro marked at 120 beats per minute and andante marked at 80 beats per minute. Allegro should certainly be quite a bit faster than andante, but it may not be exactly 120 beats per minute.

Tempo Terms

A tempo marking that is a word or phrase gives you the composer’s idea of how fast the music should feel. How fast a piece of music feels depends on several different things, including the texture and complexity of the music, how often the beat gets divided into faster notes, and how fast the beats themselves are (the metronome marking). Also, the same tempo marking can mean quite different things to different composers; if a metronome marking is not available, the performer should use a knowledge of the music’s style and genre, and musical common sense, to decide on the proper tempo. When possible, listening to a professional play the piece can help with tempo decisions, but it is also reasonable for different performers to prefer slightly different tempos for the same piece.

Traditionally, tempo instructions are given in Italian.

Some Common Tempo Markings

- Grave – very slow and solemn (pronounced “GRAH-vay”)

- Largo – slow and broad (“LAR-go”)

- Larghetto – not quite as slow as largo (“lar-GET-oh”)

- Adagio – slow (“uh-DAH-jee-oh”)

- Lento – slow (“LEN-toe”)

- Andante – literally “walking”, a medium slow tempo (“on-DON-tay”)

- Moderato – moderate, or medium (“MOD-er-AH-toe”)

- Allegretto – Not as fast as allegro (“AL-luh-GRET-oh”)

- Allegro – fast (“uh-LAY-grow”)

- Vivo, or Vivace – lively and brisk (“VEE-voh”)

- Presto – very fast (“PRESS-toe”)

- Prestissimo – very, very fast (“press-TEE-see-moe”)

These terms, along with a little more Italian, will help you decipher most tempo instructions.

More useful Italian

- (un) poco – a little (“oon POH-koe”)

- molto – a lot (“MOLE-toe”)

- piu – more (“pew”)

- meno – less (“MAY-no”)

- mosso – literally “moved”; motion or movement (“MOE-so”)

Exercise 1.13.1.

Check to see how comfortable you are with Italian tempo markings by translating the following.

- un poco allegro

- molto meno mosso

- piu vivo

- molto adagio

- poco piu mosso

Of course, tempo instructions don’t have to be given in Italian. Much folk, popular, and modern music, gives instructions in English or in the composer’s language. Tempo indications such as “Not too fast”, “With energy”, “Calmly”, or “March tempo” give a good idea of how fast the music should feel.

Gradual Tempo Changes

If the tempo of a piece of music suddenly changes into a completely different tempo, there will be a new tempo given, usually marked in the same way (metronome tempo, Italian term, etc.) as the original tempo. Gradual changes in the basic tempo are also common in music, though, and these have their own set of terms. These terms often appear below the staff, although writing them above the staff is also allowed. These terms can also appear with modifiers like molto or un poco. You may notice that there are quite a few terms for slowing down. Again, the use of these terms will vary from one composer to the next; unless beginning and ending tempo markings are included, the performer must simply use good musical judgement to decide how much to slow down in a particular ritardando or rallentando.

Gradual Tempo Changes

- accelerando – (abbreviated accel.) accelerating; getting faster

- ritardando – (abbrev. rit.) slowing down

- ritenuto – (abbrev. riten.) slower

- rallentando – (abbrev. rall.) gradually slower

- rubato – don’t be too strict with the rhythm; while keeping the basic tempo, allow the music to gently speed up and relax in ways that emphasize the phrasing

- poco a poco – little by little; gradually

- Tempo I – (“tempo one” or “tempo primo”) back to the original tempo (this instruction usually appears above the staff)

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 1.13.1.

- a little fast

- much less motion = much slower

- more lively = faster

- very slow

- a little more motion = a little faster

Repeats and Other Musical Road Map Signs*

Repetition, either exact or with small or large variations, is one of the basic organizing principles of music. Repeated notes, motifs, phrases, melodies, rhythms, chord progressions, and even entire repeated sections in the overall form, are all very crucial in helping the listener make sense of the music. So good music is surprisingly repetitive!

So, in order to save time, ink, and page turns, common notation has many ways to show that a part of the music should be repeated exactly.

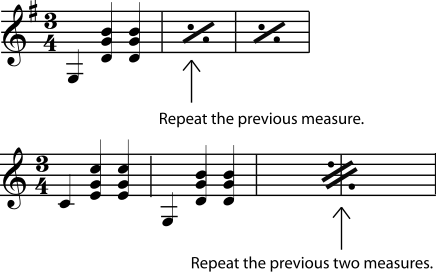

If the repeated part is very small – only one or two measures, for example – the repeat sign will probably look something like those in Figure 1.84. If you have very many such repeated measures in a row, you may want to number them (in pencil) to help you keep track of where you are in the music.

Figure 1.84. Repeated Measures

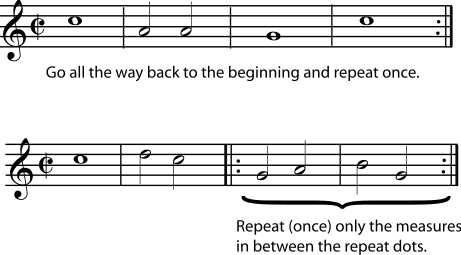

For repeated sections of medium length – usually four to thirty-two measures – repeat dots with or without endings are the most common markings. Dots to the right of a double bar line begin the repeated section; dots to the left of a double bar line end it. If there are no beginning repeat dots, you should go all the way back to the beginning of the music and repeat from there.

Figure 1.85. Repeat Dots

If there are no extra instructions, a repeated section should be played twice. Occasionally you will see extra instructions over the repeat dots, for example to play the section “3x” (three times).

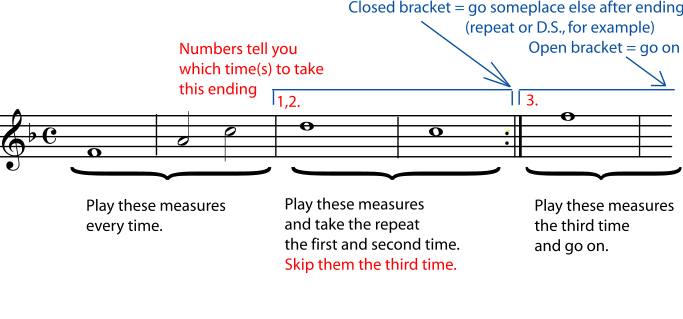

It is very common for longer repeated sections of music to be repeated exactly until the last few measures. When this happens, the repeat dots will be put in an ending. The bracket over the music shows you which measures to play each time you arrive at that point in the music. For example, the second time you reach a set of endings, you will skip the music in all the other endings; play only the measures in the second ending, and then do whatever the second ending directs you to do (repeat, go on, skip to somewhere else, etc.).

Figure 1.86. Repeat Endings

Some “endings” of a section of music may include a repeat, while others do not. Play only one ending each time (skipping over other, previously played endings when necessary), and then follow the “instructions” at the end of the ending (to repeat, go on, go someplace else, etc.).

When you are repeating large sections in more informally written music, you may simply find instructions in the music such as “to refrain”, “to bridge”, “to verses”, etc. Or you may find extra instructions to play certain parts “only on the repeat”. Usually these instructions are reasonably clear, although you may need to study the music for a minute to get the “road map” clear in your mind. Pencilled-in markings can be a big help if it’s difficult to spot the place you need to skip to. In order to help clarify things, repeat dots and other repeat instructions are almost always marked by a double bar line.

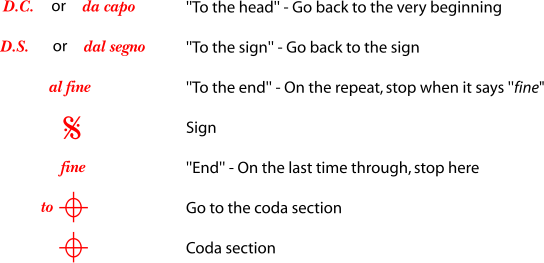

In Western classical music, the most common instructions for repeating large sections are traditionally written (or abbreviated) in Italian. The most common instructions from that tradition are in Figure 1.87.

Figure 1.87. Other Common “Road Map” Signs

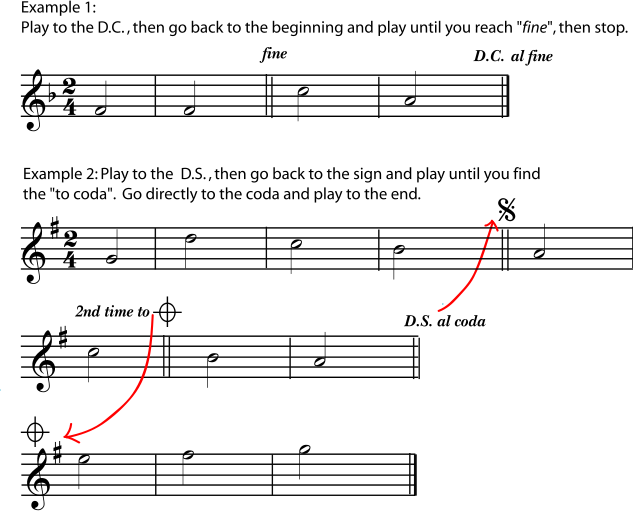

Again, instructions can easily get quite complicated, and these large-section markings may require you to study your part for a minute to see how it is laid out, and even to mark (in pencil) circles and arrows that help you find the way quickly while you are playing. Figure 1.88 contains a few very simplistic examples of how these “road map signs” will work.

Figure 1.88.

Here are some (shortened) examples of how these types of repeat instructions may be arranged. These types of signs usually mark longer repeated sections. In many styles of music, a short repeated section (usually marked with repeat dots) is often not repeated after a da capo or dal segno.