MUSIC THEORY ( DEFINITIONS, MELODY, TEXTURE )

2.1. Rhythm*

Rhythm, melody, harmony, timbre, and texture are the essential aspects of a musical performance. They are often called the basic elements of music. The main purpose of music theory is to describe various pieces of music in terms of their similarities and differences in these elements, and music is usually grouped into genres based on similarities in all or most elements. It’s useful, therefore, to be familiar with the terms commonly used to describe each element. Because harmony is the most highly developed aspect of Western music, music theory tends to focus almost exclusively on melody and harmony. Music does not have to have harmony, however, and some music doesn’t even have melody. So perhaps the other three elements can be considered the most basic components of music.

Music cannot happen without time. The placement of the sounds in time is the rhythm of a piece of music. Because music must be heard over a period of time, rhythm is one of the most basic elements of music. In some pieces of music, the rhythm is simply a “placement in time” that cannot be assigned a beat or meter, but most rhythm terms concern more familiar types of music with a steady beat. See Meter for more on how such music is organized, and Duration and Time Signature for more on how to read and write rhythms. See Simple Rhythm Activities for easy ways to encourage children to explore rhythm.

Rhythm Terms

- Rhythm – The term “rhythm” has more than one meaning. It can mean the basic, repetitive pulse of the music, or a rhythmic pattern that is repeated throughout the music (as in “feel the rhythm”). It can also refer to the pattern in time of a single small group of notes (as in “play this rhythm for me”).

- Beat – Beat also has more than one meaning, but always refers to music with a steady pulse. It may refer to the pulse itself (as in “play this note on beat two of the measure”). On the beat or on the downbeat refer to the moment when the pulse is strongest. Off the beat is in between pulses, and the upbeat is exactly halfway between pulses. Beat may also refer to a specific repetitive rhythmic pattern that maintains the pulse (as in “it has a Latin beat”). Note that once a strong feeling of having a beat is established, it is not necessary for something to happen on every beat; a beat can still be “felt” even if it is not specifically heard.

- Measure or bar – Beats are grouped into measures or bars. The first beat is usually the strongest, and in most music, most of the bars have the same number of beats. This sets up an underlying pattern in the pulse of the music: for example, strong-weak-strong-weak-strong-weak, or strong-weak-weak-strong-weak-weak. (See Meter.)

- Rhythm Section – The rhythm section of a band is the group of instruments that usually provide the background rhythm and chords. The rhythm section almost always includes a percussionist (usually on a drum set) and a bass player (usually playing a plucked string bass of some kind). It may also include a piano and/or other keyboard players, more percussionists, and one or more guitar players or other strummed or plucked strings. Vocalists, wind instruments, and bowed strings are usually not part of the rhythm section.

- Syncopation – Syncopation occurs when a strong note happens either on a weak beat or off the beat. See Syncopation.

2.2. Timbre*

One of the basic elements of music is called color, or timbre (pronounced “TAM-ber”). Timbre describes all of the aspects of a musical sound that do not have anything to do with the sound’s pitch, loudness, or length. In other words, if a flute plays a note, and then an oboe plays the same note, for the same length of time, at the same loudness, you can still easily distinguish between the two sounds, because a flute sounds different from an oboe. This difference is in the timbre of the sounds.

Timbre is caused by the fact that each note from a musical instrument is a complex wave containing more than one frequency. For instruments that produce notes with a clear and specific pitch, the frequencies involved are part of a harmonic series. For other instruments (such as drums), the sound wave may have an even greater variety of frequencies. We hear each mixture of frequencies not as separate sounds, but as the color of the sound. Small differences in the balance of the frequencies – how many you can hear, their relationship to the fundamental pitch, and how loud they are compared to each other – create the many different musical colors.

The harmonics at the beginning of each note – the attack – are especially important for timbre, so it is actually easier to identify instruments that are playing short notes with strong articulations than it is to identify instruments playing long, smooth notes.

The human ear and brain are capable of hearing and appreciating very small variations in timbre. A listener can hear not only the difference between an oboe and a flute, but also the difference between two different oboes. The general sound that one would expect of a type of instrument – a trombone for example – is usually called its timbre or color. Variations in timbre between specific instruments – two different trombones, for example, or two different trombone players, or the same trombone player using different types of sound in different pieces – may be called differences in timbre or color, or may be called differences in tone or in tone quality. Tone quality may refer specifically to “quality”, as when a young trombonist is encouraged to have a “fuller” or “more focussed” tone quality, or it can refer neutrally to differences in sound, as when an orchestral trombonist is asked to play with a “brassy” tone quality in one passage and a “mellow” tone quality in another.

Many words are used to describe timbre. Some are somewhat interchangeable, and some may have slightly different meanings for different musicians, so no attempt will be made to provide definitions. Here are a few words commonly used to describe either timbre or tone quality.

- Reedy

- Brassy

- Clear

- Focussed or unfocussed

- Breathy (pronounced “BRETH-ee”)

- Rounded

- Piercing

- Strident

- Harsh

- Warm

- Mellow

- Resonant

- Dark or Bright

- Heavy or Light

- Flat

- Having much, little, or no vibrato (a controlled wavering in the sound); or narrow or wide, or slow or fast, vibrato

For more information on what causes timbre, please see Harmonic Series I, Standing Waves and Musical Instruments, and Standing Waves and Wind Instruments.) For activities that introduce children to the concept of timbre, please see Timbre Activities

2.3. Melody*

Introduction

Melody is one of the most basic elements of music. A note is a sound with a particular pitch and duration. String a series of notes together, one after the other, and you have a melody. But the melody of a piece of music isn’t just any string of notes. It’s the notes that catch your ear as you listen; the line that sounds most important is the melody. There are some common terms used in discussions of melody that you may find it useful to know. First of all, the melodic line of a piece of music is the string of notes that make up the melody. Extra notes, such as trills and slides, that are not part of the main melodic line but are added to the melody either by the composer or the performer to make the melody more complex and interesting are called ornaments or embellishments. Below are some more concepts that are associated with melody.

The Shape or Contour of a Melody

A melody that stays on the same pitch gets boring pretty quickly. As the melody progresses, the pitches may go up or down slowly or quickly. One can picture a line that goes up steeply when the melody suddenly jumps to a much higher note, or that goes down slowly when the melody gently falls. Such a line gives the contour or shape of the melodic line. You can often get a good idea of the shape of this line by looking at the melody as it is written on the staff, but you can also hear it as you listen to the music.

Figure 2.1.

Arch shapes (in which the melody rises and then falls) are easy to find in many melodies.

You can also describe the shape of a melody verbally. For example, you can speak of a “rising melody” or of an “arch-shaped” phrase. Please see The Shape of a Melody for children’s activities covering melodic contour.

Melodic Motion

Another set of useful terms describe how quickly a melody goes up and down. A melody that rises and falls slowly, with only small pitch changes between one note and the next, is conjunct. One may also speak of such a melody in terms of step-wise or scalar motion, since most of the intervals in the melody are half or whole steps or are part of a scale.

A melody that rises and falls quickly, with large intervals between one note and the next, is a disjunct melody. One may also speak of “leaps” in the melody. Many melodies are a mixture of conjunct and disjunct motion.

Figure 2.2.

A melody may show conjuct motion, with small changes in pitch from one note to the next, or disjunct motion, with large leaps. Many melodies are an interesting, fairly balanced mixture of conjunct and disjunct motion.

Melodic Phrases

Melodies are often described as being made up of phrases. A musical phrase is actually a lot like a grammatical phrase. A phrase in a sentence (for example, “into the deep, dark forest” or “under that heavy book”) is a group of words that make sense together and express a definite idea, but the phrase is not a complete sentence by itself. A melodic phrase is a group of notes that make sense together and express a definite melodic “idea”, but it takes more than one phrase to make a complete melody.

How do you spot a phrase in a melody? Just as you often pause between the different sections in a sentence (for example, when you say, “wherever you go, there you are”), the melody usually pauses slightly at the end of each phrase. In vocal music, the musical phrases tend to follow the phrases and sentences of the text. For example, listen to the phrases in the melody of “The Riddle Song” and see how they line up with the four sentences in the song.

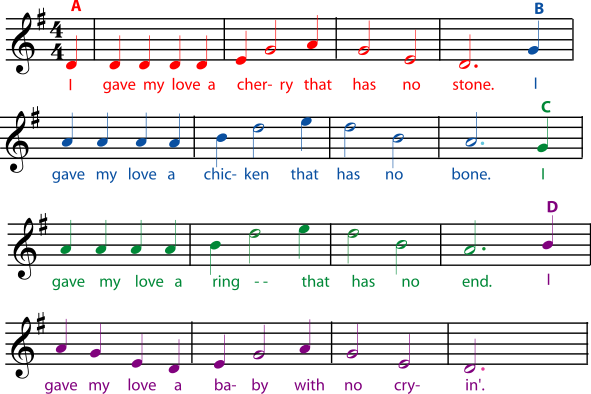

Figure 2.3. The Riddle Song

This melody has four phrases, one for each sentence of the text.

But even without text, the phrases in a melody can be very clear. Even without words, the notes are still grouped into melodic “ideas”. Listen to the first strain of Scott Joplin’s “The Easy Winners” to see if you can hear four phrases in the melody.

One way that a composer keeps a piece of music interesting is by varying how strongly the end of each phrase sounds like “the end”. Usually, full-stop ends come only at the end of the main sections of the music. (See form and cadence for more on this.) By varying aspects of the melody, the rhythm, and the harmony, the composer gives the ends of the other phrases stronger or weaker “ending” feelings. Often, phrases come in definite pairs, with the first phrase feeling very unfinished until it is completed by the second phrase, as if the second phrase were answering a question asked by the first phrase. When phrases come in pairs like this, the first phrase is called the antecedent phrase, and the second is called the consequent phrase. Listen to antecedent and consequent phrases in the tune “Auld Lang Syne”.

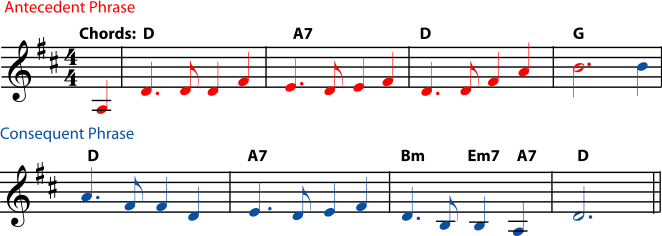

Figure 2.4. Antecedent and Consequent Phrases

The rhythm of the first two phrases of “Auld Lang Syne” is the same, but both the melody and the harmony lead the first phrase to feel unfinished until it is answered by the second phrase. Note that both the melody and harmony of the second phrase end on the tonic, the “home” note and chord of the key.

Of course, melodies don’t always divide into clear, separated phrases. Often the phrases in a melody will run into each other, cut each other short, or overlap. This is one of the things that keeps a melody interesting.

Motif

Another term that usually refers to a piece of melody (although it can also refer to a rhythm or a chord progression) is “motif”. A motif is a short musical idea – shorter than a phrase – that occurs often in a piece of music. A short melodic idea may also be called a motiv, a motive, a cell, or a figure. These small pieces of melody will appear again and again in a piece of music, sometimes exactly the same and sometimes changed. When a motif returns, it can be slower or faster, or in a different key. It may return “upside down” (with the notes going up instead of down, for example), or with the pitches or rhythms altered.

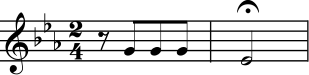

Figure 2.5.

The “fate motif” from the first movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. This is a good example of a short melodic idea (a cell, motive, or figure) that is used in many different ways throughout the movement.

Most figures and motifs are shorter than phrases, but some of the leitmotifs of Wagner’s operas are long enough to be considered phrases. A leitmotif (whether it is a very short cell or a long phrase) is associated with a particular character, place, thing, or idea in the opera and may be heard whenever that character is on stage or that idea is an important part of the plot. As with other motifs, leitmotifs may be changed when they return. For example, the same melody may sound quite different depending on whether the character is in love, being heroic, or dying.

Figure 2.6.

A melodic phrase based on the Siegfried leitmotif, from Wagner’s opera The Valkyrie.

Melodies in Counterpoint

Counterpoint has more than one melody at the same time. This tends to change the rules for using and developing melodies, so the terms used to talk about contrapuntal melodies are different, too. For example, the melodic idea that is most important in a fugue is called its subject. Like a motif, a subject has often changed when it reappears, sounding higher or lower, for example, or faster or slower. For more on the subject (pun intended), please see Counterpoint.

Themes

A longer section of melody that keeps reappearing in the music – for example, in a “theme and variations” – is often called a theme. Themes generally are at least one phrase long and often have several phrases. Many longer works of music, such as symphony movements, have more than one melodic theme.

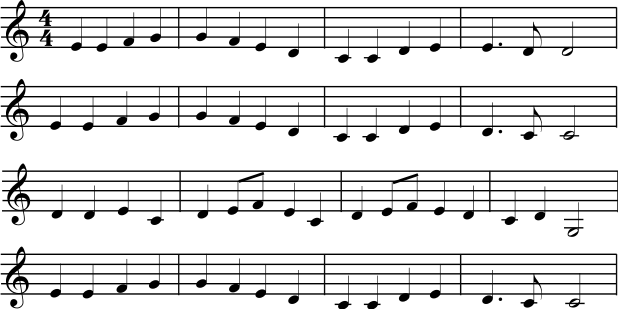

Figure 2.7. Theme from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9

The tune of this theme will be very familiar to most people, but you may want to listen to the entire last movement of the symphony to hear the different ways that Beethoven uses the melody again and again.

The musical scores for movies and television can also contain melodic themes, which can be developed as they might be in a symphony or may be used very much like operatic leitmotifs. For example, in the music John Williams composed for the Star Wars movies, there are melodic themes that are associated with the main characters. These themes are often complete melodies with many phrases, but a single phrase can be taken from the melody and used as a motif. A single phrase of Ben Kenobi’s Theme, for example, can remind you of all the good things he stands for, even if he is not on the movie screen at the time.

Suggestions for Presenting these Concepts to Children

Melody is a particularly easy concept to convey to children, since attention to a piece of music is naturally drawn to the melody. If you would like to introduce some of these concepts and terms to children, please see A Melody Activity, The Shape of a Melody, Melodic Phrases, and Theme and Motif in Music.

2.4. Texture*

Introduction

Texture is one of the basic elements of music. When you describe the texture of a piece of music, you are describing how much is going on in the music at any given moment. For example, the texture of the music might be thick or thin, or it may have many or few layers. It might be made up of rhythm only, or of a melody line with chordal accompaniment, or many interweaving melodies. Below you will find some of the formal terms musicians use to describe texture. Suggestions for activities to introduce the concept of texture to young students can be found in Musical Textures Activities.

Terms that Describe Texture

There are many informal terms that can describe the texture of a piece of music (thick, thin, bass-heavy, rhythmically complex, and so on), but the formal terms that are used to describe texture all describe the relationships of melodies and harmonies. Here are definitions and examples of the four main types of texture. For specific pieces of music that are good examples of each type of texture, please see below.

Monophonic

Monophonic music has only one melodic line, with no harmony or counterpoint. There may be rhythmic accompaniment, but only one line that has specific pitches. Monophonic music can also be called monophony. It is sometimes called monody, although the term “monody” can also refer to a particular type of solo song (with instrumental accompaniment) that was very popular in the 1600’s.

Examples of Monophony

- One person whistling a tune

- A single bugle sounding “Taps”

- A group of people all singing a song together, without harmonies or instruments

- A fife and drum corp, with all the fifes playing the same melody

Homophonic

Homophonic music can also be called homophony. More informally, people who are describing homophonic music may mention chords, accompaniment, harmony or harmonies. Homophony has one clearly melodic line; it’s the line that naturally draws your attention. All other parts provide accompaniment or fill in the chords. In most well-written homophony, the parts that are not melody may still have a lot of melodic interest. They may follow many of the rules of well-written counterpoint, and they can sound quite different from the melody and be interesting to listen to by themselves. But when they are sung or played with the melody, it is clear that they are not independent melodic parts, either because they have the same rhythm as the melody (i.e. are not independent) or because their main purpose is to fill in the chords or harmony (i.e. they are not really melodies).

Examples of Homophony

- Choral music in which the parts have mostly the same rhythms at the same time is homophonic. Most traditional Protestant hymns and most “barbershop quartet” music is in this category.

- A singer accompanied by a guitar picking or strumming chords.

- A small jazz combo with a bass, a piano, and a drum set providing the “rhythm” background for a trumpet improvising a solo.

- A single bagpipes or accordion player playing a melody with drones or chords.

Polyphonic

Polyphonic music can also be called polyphony, counterpoint, or contrapuntal music. If more than one independent melody is occurring at the same time, the music is polyphonic. (See counterpoint.)

Examples of Polyphony

- Rounds, canons, and fugues are all polyphonic. (Even if there is only one melody, if different people are singing or playing it at different times, the parts sound independent.)

- Much Baroque music is contrapuntal, particularly the works of J.S. Bach.

- Most music for large instrumental groups such as bands or orchestras is contrapuntal at least some of the time.

- Music that is mostly homophonic can become temporarily polyphonic if an independent countermelody is added. Think of a favorite pop or gospel tune that, near the end, has the soloist “ad libbing” while the back-up singers repeat the refrain.

Heterophonic

A heterophonic texture is rare in Western music. In heterophony, there is only one melody, but different variations of it are being sung or played at the same time.

- Heterophony can be heard in the Bluegrass, “mountain music”, Cajun, and Zydeco traditions. Listen for the tune to be played by two instruments (say fiddle and banjo) at the same time, with each adding the embellishments, ornaments, and flourishes that are characteristic of the instrument.

- Some Middle Eastern, South Asian, central Eurasian, and Native American music traditions include heterophony. Listen for traditional music (most modern-composed music, even from these cultures, has little or no heterophony) in which singers and/or instrumentalists perform the same melody at the same time, but give it different embellishments or ornaments.

Suggested Listening

Monophony

- Any singer performing alone

- Any orchestral woodwind or brass instrument (flute, clarinet, trumpet, trombone, etc.) performing alone. Here is an example from James Romig’s Sonnet 2, played by John McMurtery.

- A Bach unaccompanied cello suite

- Gregorian chant

- Most fife and drum music

- Long sections of “The People that Walked in Darkness” aria in Handel’s “Messiah” are monophonic (the instruments are playing the same line as the voice). Apparently Handel associates monophony with “walking in darkness”!

- Monophony is very unusual in contemporary popular genres, but can be heard in Queen’s “We Will Rock You.”

Homophony

- A classic Scott Joplin rag such as “Maple Leaf Rag” or “The Entertainer”

- The “graduation march” section of Edward Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance No. 1”

- The “March of the Toreadors” from Bizet’s Carmen

- No. 1 (“Granada”) of Albeniz’ Suite Espanola for guitar

- Most popular music genres strongly favor homophonic textures, whether featuring a solo singer, rapper, guitar solo, or several vocalists singing in harmony.

- The opening section of the “Overture” Of Handel’s “Messiah” (The second section of the overture is polyphonic)

Polyphony

- Pachelbel’s Canon

- Anything titled “fugue” or “invention”

- The final “Amen” chorus of Handel’s “Messiah”

- The trio strain of Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever”, with the famous piccolo countermelody

- The “One Day More” chorus from the musical “Les Miserables”

- The first movement of Holst’s 1st Suite for Military Band

- Polyphony is rare in contemporary popular styles, but examples of counterpoint can be found, including the refrain of the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations,” the second through fourth verses of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Scarborough Fair/Canticle,” the final refrain of Jason Mraz’s “I’m Yours,” and the horn counterpoint in Ghost of a Saber Tooth Tiger’s “Lavender Road.”

Heterophony

- There is some heterophony (with some instruments playing more ornaments than others) in “Donulmez Aksamin” and in “Urfaliyim Ezelden” on the Turkish Music page. You can also try simply searching for “heterophony” at YouTube or other sites with large collections of recordings.

- The performance of “Lonesome Valley” by the Fairfield Four on the “O Brother, Where Art Thou” soundtrack is quite heterophonic.