HALF STEPS AND WHOLE STEPS, MAJOR AND MINOR KEYS AND SCALES

4.2. Half Steps and Whole Steps*

The pitch of a note is how high or low it sounds. Musicians often find it useful to talk about how much higher or lower one note is than another. This distance between two pitches is called the interval between them. In Western music, the small interval from one note to the next closest note higher or lower is called a half step or semi-tone.

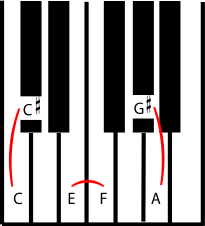

Figure 4.8. Half Steps

(a)

(b)Three half-step intervals: between C and C sharp (or D flat); between E and F; and between G sharp (or A flat) and A.

Listen to the half steps in Figure 4.8.

The intervals in Figure 4.8 look different on a staff; sometimes they are on the same line, sometimes not. But it is clear at the keyboard that in each case there is no note in between them.

So a scale that goes up or down by half steps, a chromatic scale, plays all the notes on both the white and black keys of a piano. It also plays all the notes easily available on most Western instruments. (A few instruments, like trombone and violin, can easily play pitches that aren’t in the chromatic scale, but even they usually don’t.)

Figure 4.9. One Octave Chromatic Scale

All intervals in a chromatic scale are half steps. The result is a scale that plays all the notes easily available on most instruments.

Listen to a chromatic scale.

If you go up or down two half steps from one note to another, then those notes are a whole step, or whole tone apart.

Figure 4.10. Whole Steps

(a)

(b)Three whole step intervals: between C and D; between E and F sharp; and between G sharp and A sharp (or A flat and B flat).

A whole tone scale, a scale made only of whole steps, sounds very different from a chromatic scale.

Figure 4.11. Whole Tone Scale

All intervals in a whole tone scale are whole steps.

Listen to a whole tone scale.

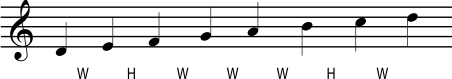

You can count any number of whole steps or half steps between notes; just remember to count all sharp or flat notes (the black keys on a keyboard) as well as all the natural notes (the white keys) that are in between.

Example 4.2.

The interval between C and the F above it is 5 half steps, or two and a half steps.

Figure 4.12.

Going from C up to F takes five half steps.

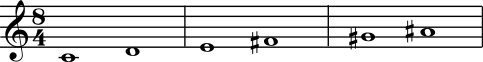

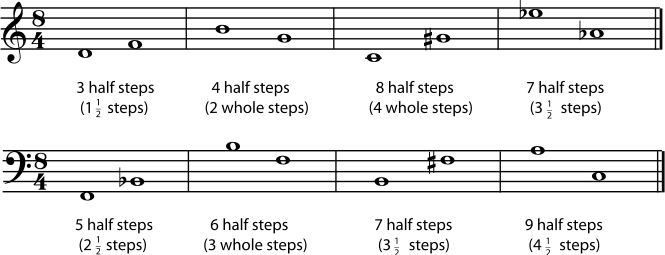

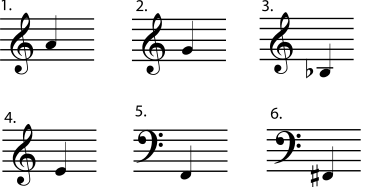

Exercise 4.2.1.

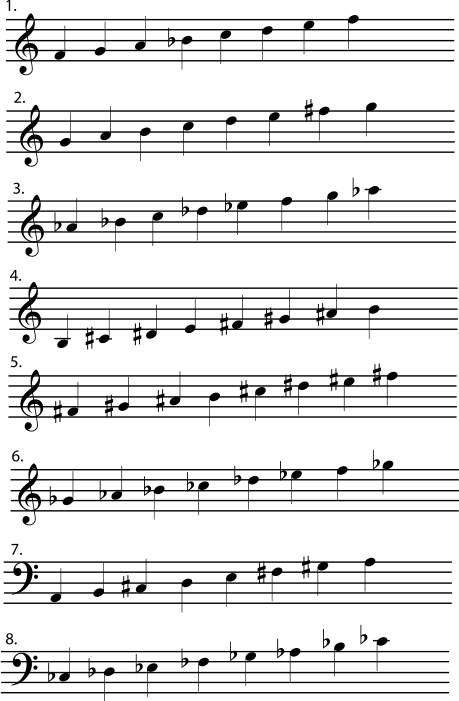

Identify the intervals below in terms of half steps and whole steps. If you have trouble keeping track of the notes, use a piano keyboard, a written chromatic scale, or the chromatic fingerings for your instrument to count half steps.

Figure 4.13.

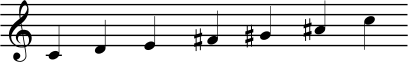

Exercise 4.2.2.

Fill in the second note of the interval indicated in each measure. If you need staff paper for this exercise, you can print out this staff paper PDF file.

Figure 4.14.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 4.2.1.

Figure 4.15.

Solution to Exercise 4.2.2.

Figure 4.16.

If your answer is different, check to see if you have written a different enharmonic spelling of the note in the answer. For example, the B flat could be written as an A sharp.

4.3. Major Keys and Scales*

The simple, sing-along, nursery rhymes and folk songs we learn as children; the “catchy” tunes used in advertising jingles; the cheerful, toe-tapping pop and rock we dance to; the uplifting sounds of a symphony: most music in a major key has a bright sound that people often describe as cheerful, inspiring, exciting, or just plain fun.

How are these moods produced? Music in a particular key tends to use only some of the many possible notes available; these notes are listed in the scale associated with that key. In major keys, the notes of the scale are often used to build “bright”-sounding major chords. They also give a strong feeling of having a tonal center, a note or chord that feels like “home”, or “the resting place”, in that key. The “bright”-sounding major chords and the strong feeling of tonality are what give major keys their happy, pleasant moods. This contrasts with the moods usually suggested by music that uses minor keys, scales, and chords. Although it also has a strong tonal center (the Western tradition of tonal harmony is based on major and minor keys and scales), music in a minor key is more likely to sound sad, ominous, or mysterious. In fact, most musicians, and even many non-musicians, can distinguish major and minor keys just by listening to the music.

Exercise 4.3.1.

Listen to these excerpts. Three are in a major key and two in a minor key. Can you tell which is which simply by listening?

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

Note

If you must determine whether a piece of music is major or minor, and cannot tell just by listening, you may have to do some simple harmonic analysis in order to decide.

Tonal Center

A scale starts with the note that names the key. This note is the tonal center of that key, the note where music in that key feels “at rest”. It is also called the tonic, and it’s the “do” in “do-re-mi”. For example, music in the key of A major almost always ends on an A major chord, the chord built on the note A. It often also begins on that chord, returns to that chord often, and features a melody and a bass line that also return to the note A often enough that listeners will know where the tonal center of the music is, even if they don’t realize that they know it. (For more information about the tonic chord and its relationship to other chords in a key, please see Beginning Harmonic Analysis.)

Example 4.3.

Listen to these examples. Can you hear that they do not feel “done” until the final tonic is played?

- Example A

- Example B

Major Scales

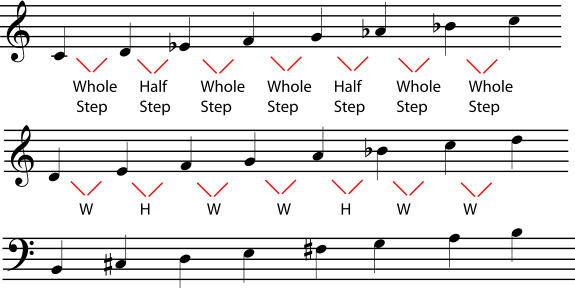

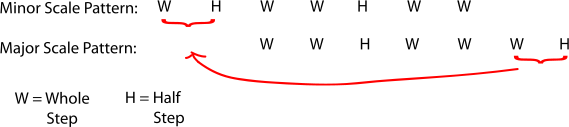

To find the rest of the notes in a major key, start at the tonic and go up following this pattern: whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step. This will take you to the tonic one octave higher than where you began, and includes all the notes in the key in that octave.

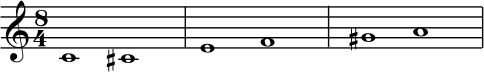

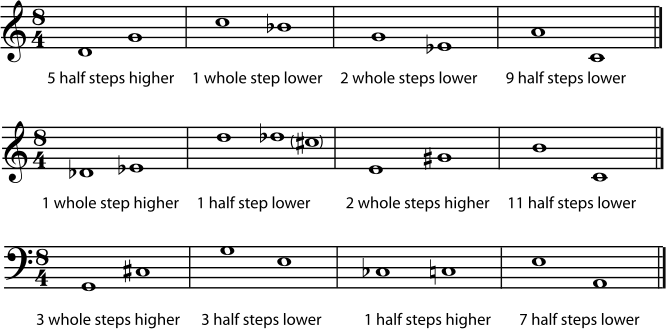

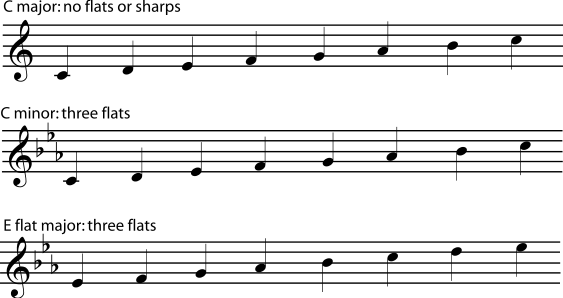

Example 4.4.

These major scales all follow the same pattern of whole steps and half steps. They have different sets of notes because the pattern starts on different notes.

Figure 4.17. Three Major Scales

All major scales have the same pattern of half steps and whole steps, beginning on the note that names the scale – the tonic.

Listen to the difference between the C major, D major, and B flat major scales.

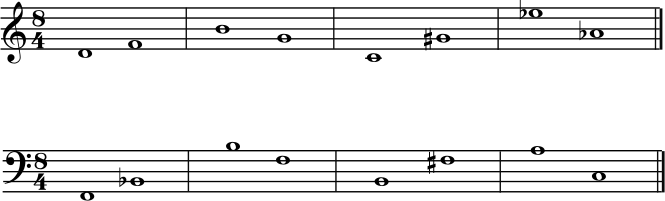

Exercise 4.3.2.

For each note below, write a major scale, one octave, ascending (going up), beginning on that note. If you’re not sure whether a note should be written as a flat, sharp, or natural, remember that you won’t ever skip a line or space, or write two notes of the scale on the same line or space. If you need help keeping track of half steps, use a keyboard, a picture of a keyboard, a written chromatic scale, or the chromatic scale fingerings for your instrument. If you need more information about half steps and whole steps, see Half Steps and Whole Steps.

If you need staff paper for this exercise, you can print out this staff paper PDF file.

Figure 4.18.

In the examples above, the sharps and flats are written next to the notes. In common notation, the sharps and flats that belong in the key will be written at the beginning of each staff, in the key signature. For more practice identifying keys and writing key signatures, please see Key Signature. For more information about how keys are related to each other, please see The Circle of Fifths.Note

Do key signatures make music more complicated than it needs to be? Is there an easier way? Join the discussion at Opening Measures.

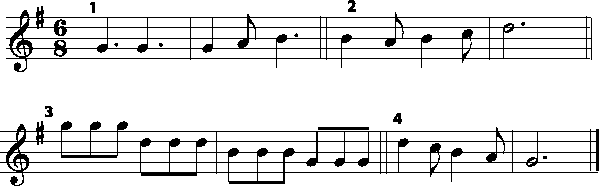

Music in Different Major Keys

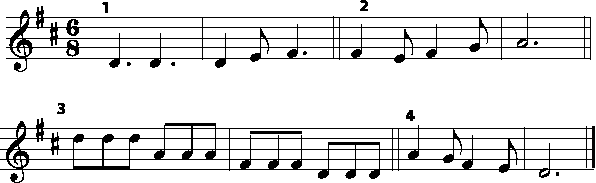

What difference does key make? Since the major scales all follow the same pattern, they all sound very much alike. Here is the tune “Row, Row, Row Your Boat”, written in G major and also in D major.

Figure 4.19.

(a) In G Major

(b) In D MajorThe same tune looks very different when written in two different major keys.

Listen to this tune in G major and in D major. The music may look quite different, but the only difference when you listen is that one sounds higher than the other. So why bother with different keys at all? Before equal temperament became the standard tuning system, major keys sounded more different from each other than they do now. Even now, there are subtle differences between the sound of a piece in one key or another, mostly because of differences in the timbre of various notes on the instruments or voices involved. But today the most common reason to choose a particular key is simply that the music is easiest to sing or play in that key. (Please see Transposition for more about choosing keys.)

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 4.3.1.

- Major

- Major

- Minor

- Major

- Minor

Solution to Exercise 4.3.2.

Figure 4.20.

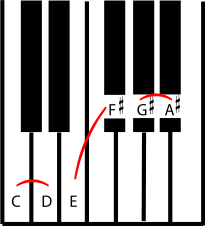

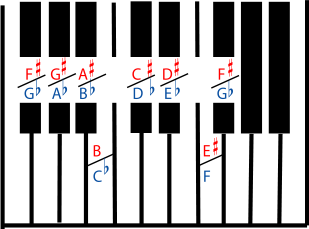

Notice that although they look completely different, the scales of F sharp major and G flat major (numbers 5 and 6) sound exactly the same when played, on a piano as shown in Figure 4.21, or on any other instrument using equal temperament tuning. If this surprises you, please read more about enharmonic scales.

Figure 4.21. Enharmonic Scales

Using this figure of a keyboard, or the fingerings from your own instrument, notice that the notes for the F sharp major scale and the G flat major scale in Figure 4.20, although spelled differently, will sound the same.

4.4. Minor Keys and Scales*

Music in a Minor Key

Each major key uses a different set of notes (its major scale). In each major scale, however, the notes are arranged in the same major scale pattern and build the same types of chords that have the same relationships with each other. (See Beginning Harmonic Analysis for more on this.) So music that is in, for example, C major, will not sound significantly different from music that is in, say, D major. But music that is in D minor will have a different quality, because the notes in the minor scale follow a different pattern and so have different relationships with each other. Music in minor keys has a different sound and emotional feel, and develops differently harmonically. So you can’t, for example, transpose a piece from C major to D minor (or even to C minor) without changing it a great deal. Music that is in a minor key is sometimes described as sounding more solemn, sad, mysterious, or ominous than music that is in a major key. To hear some simple examples in both major and minor keys, see Major Keys and Scales.

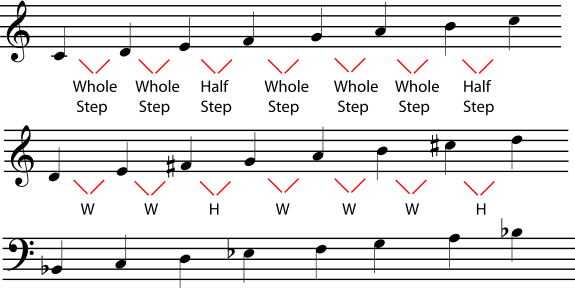

Minor Scales

Minor scales sound different from major scales because they are based on a different pattern of intervals. Just as it did in major scales, starting the minor scale pattern on a different note will give you a different key signature, a different set of sharps or flats. The scale that is created by playing all the notes in a minor key signature is a natural minor scale. To create a natural minor scale, start on the tonic note and go up the scale using the interval pattern: whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step.

Figure 4.22. Natural Minor Scale Intervals

Listen to these minor scales.

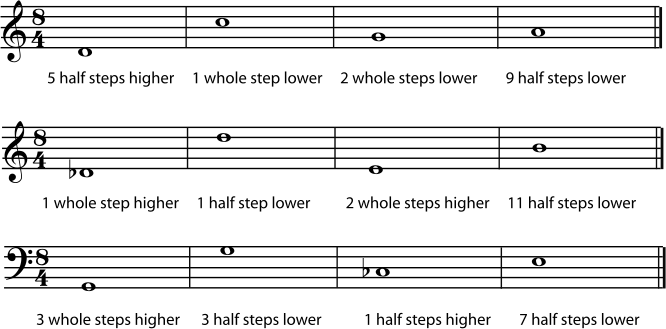

Exercise 4.4.1.

For each note below, write a natural minor scale, one octave, ascending (going up) beginning on that note. If you need staff paper, you may print the staff paper PDF file.

Figure 4.23.

Relative Minor and Major Keys

Each minor key shares a key signature with a major key. A minor key is called the relative minor of the major key that has the same key signature. Even though they have the same key signature, a minor key and its relative major sound very different. They have different tonal centers, and each will feature melodies, harmonies, and chord progressions built around their (different) tonal centers. In fact, certain strategic accidentals are very useful in helping establish a strong tonal center in a minor key. These useful accidentals are featured in the melodic minor and harmonic minor scales.

Figure 4.24. Comparing Major and Minor Scale Patterns

The interval patterns for major and natural minor scales are basically the same pattern starting at different points.

It is easy to predict where the relative minor of a major key can be found. Notice that the pattern for minor scales overlaps the pattern for major scales. In other words, they are the same pattern starting in a different place. (If the patterns were very different, minor key signatures would not be the same as major key signatures.) The pattern for the minor scale starts a half step plus a whole step lower than the major scale pattern, so a relative minor is always three half steps lower than its relative major. For example, C minor has the same key signature as E flat major, since E flat is a minor third higher than C.

Figure 4.25. Relative Minor

The C major and C minor scales start on the same note, but have different key signatures. C minor and E flat major start on different notes, but have the same key signature. C minor is the relative minor of E flat major.

Exercise 4.4.2.

What are the relative majors of the minor keys in Figure 4.23?

Harmonic and Melodic Minor Scales

Note

Do key signatures make music more complicated than it needs to be? Is there an easier way? Join the discussion at Opening Measures.

All of the scales above are natural minor scales. They contain only the notes in the minor key signature. There are two other kinds of minor scales that are commonly used, both of which include notes that are not in the key signature. The harmonic minor scaleraises the seventh note of the scale by one half step, whether you are going up or down the scale. Harmonies in minor keys often use this raised seventh tone in order to make the music feel more strongly centered on the tonic. (Please see Beginning Harmonic Analysis for more about this.) In the melodic minor scale, the sixth and seventh notes of the scale are each raised by one half step when going up the scale, but return to the natural minor when going down the scale. Melodies in minor keys often use this particular pattern of accidentals, so instrumentalists find it useful to practice melodic minor scales.

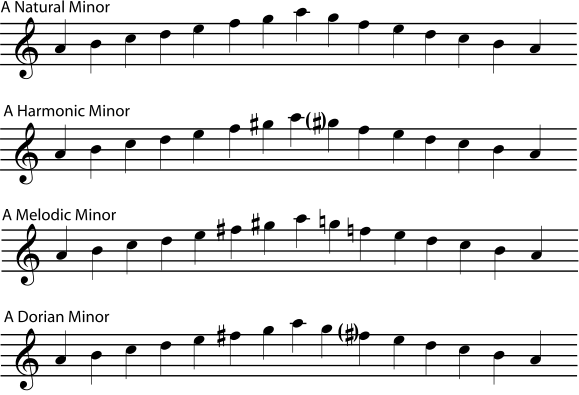

Figure 4.26. Comparing Types of Minor Scales

Listen to the differences between the natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor scales.

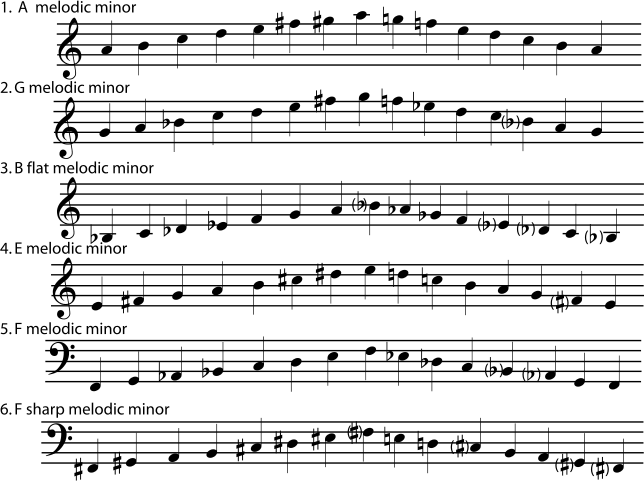

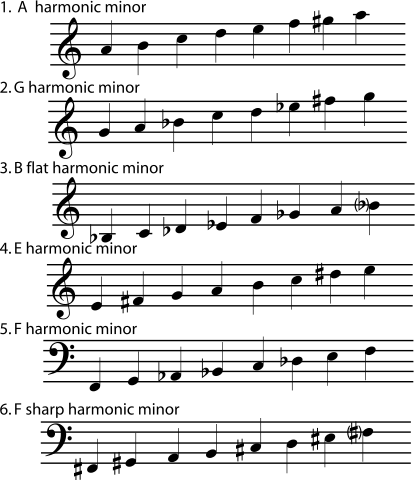

Exercise 4.4.3.

Rewrite each scale from Figure 4.23 as an ascending harmonic minor scale.

Exercise 4.4.4.

Rewrite each scale from Figure 4.23 as an ascending and descending melodic minor scale.

Jazz and “Dorian Minor”

Major and minor scales are traditionally the basis for Western Music, but jazz theory also recognizes other scales, based on the medieval church modes, which are very useful for improvisation. One of the most useful of these is the scale based on the dorian mode, which is often called the dorian minor, since it has a basically minor sound. Like any minor scale, dorian minor may start on any note, but like dorian mode, it is often illustrated as natural notes beginning on d.

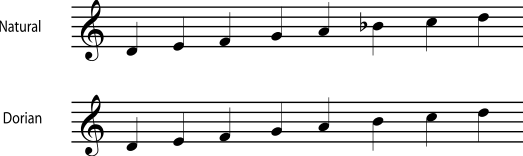

Figure 4.27. Dorian Minor

The “dorian minor” can be written as a scale of natural notes starting on d. Any scale with this interval pattern can be called a “dorian minor scale”.

Comparing this scale to the natural minor scale makes it easy to see why the dorian mode sounds minor; only one note is different.

Figure 4.28. Comparing Dorian and Natural Minors

You may find it helpful to notice that the “relative major” of the Dorian begins one whole step lower. (So, for example, D Dorian has the same key signature as C major.) In fact, the reason that Dorian is so useful in jazz is that it is the scale used for improvising while a ii chord is being played (for example, while a d minor chord is played in the key of C major), a chord which is very common in jazz. (See Beginning Harmonic Analysis for more about how chords are classified within a key.) The student who is interested in modal jazz will eventually become acquainted with all of the modal scales. Each of these is named for the medieval church mode which has the same interval pattern, and each can be used with a different chord within the key. Dorian is included here only to explain the common jazz reference to the “dorian minor” and to give notice to students that the jazz approach to scales can be quite different from the traditional classical approach.

Figure 4.29. Comparison of Dorian and Minor Scales

You may also find it useful to compare the dorian with the minor scales from Figure 4.26. Notice in particular the relationship of the altered notes in the harmonic, melodic, and dorian minors.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 4.4.1.

Figure 4.30.

Solution to Exercise 4.4.2.

- A minor: C major

- G minor: B flat major

- B flat minor: D flat major

- E minor: G major

- F minor: A flat major

- F sharp minor: A major

Solution to Exercise 4.4.3.

Figure 4.31.

Solution to Exercise 4.4.4.

Figure 4.32.